Cyber Apocalypse CTF 2021 | Part 2

In the second part of our wrap-up after the success of Cyber Apocalypse CTF 2021, we break down the four hardest challenges we included. RuneScape was a challenge based on the Imai-Matsumoto cryptosystem. Tetris 3D built on the classic cipher given in Tetris. Hyper Metroid required computing the order of the Jacobian of a special class of hyperelliptic curves and SpongeBob SquarePants was a backdoored sponge hash collision. We loved making these challenges and hope you enjoy the write-up.

If you’re looking for the solutions to the easy, medium and hard challenges, check out part 1 of our blog post.

Contents

| Challenge Name | Category | Difficulty | Solves |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nintendo Base64 | Encoding | Easy | 1928 |

| PhaseStream | XOR Encryption | Easy | 1217 |

| PhaseStream 2 | XOR Encryption | Easy | 919 |

| PhaseStream 3 | AES CTR | Easy | 531 |

| SoulCrabber | 🦀 / RNG | Easy | 432 |

| PhaseStream 4 | AES CTR | Medium | 334 |

| SoulCrabber II | 🦀 / RNG | Medium | 229 |

| RSA Jam | Carmichael lambda | Medium | 146 |

| Super Metroid | Elliptic group order | Medium | 77 |

| Forge of Empires | Elgamal message forgery | Medium | 95 |

| Tetris | Classical ciphers | Medium | 75 |

| Little Nightmares | Fermat’s little theorem | Medium | 86 |

| Wii Phit | Erdős-Straus conjecture | Hard | 38 |

| RuneScape | Imai-Matsumoto implementation | Insane | 20 |

| Tetris 3D | Classical ciphers | Insane | 18 |

| Hyper Metroid | Hyperelliptic group order | Insane | 18 |

| SpongeBob SquarePants | Sponge hash collision | Insane | 61 |

Insane

RuneScape

Authors: Robin & Jack

This is an old game, and seeing how big the output file is, I understand where the M in MMO comes from…

The main difficulty for this challenge is not actually in breaking the cryptography (which we will cover further on), but rather in reading, understanding and implementing the presented math and cryptoscheme. As such, it was originally intended as a 3⭐ challenge, but considering the target audience on the HackTheBox platform was likely to be very intimidated by the math in the pdf, we decided it would probably fit better as 4⭐.

The presented cryptosystem is a (slightly simplified) version of the scheme by Imai and Matsumoto. The main part of the implementation comes down to converting between different representations of the values we’re working with, doing matrix multiplication, and exponentiation over a finite field.

It’s tricky to elaborate a lot further on the math side of this without having too much of a repetition of the content of the pdf itself. Rather, we will briefly elaborate on the only part that was required to actually break it/solve the challenge. First, notice that generating the public key is a major pain, and is not actually required to solve the challenge. We can simply use the private key representation and use it “in the other direction” to perform the public key action. The public key that is embedded in the provided file is also entirely superfluous otherwise. The only part of the private key we’re missing is $\theta$ or $h = q^\theta + 1$. Since $q^n + 1 \equiv 1 \pmod{q^n}$ (where $q^n$ is used as a modulus because that is the size of the field we work in), this already leaves at most $n$ potential privates keys. When we further restrict this to values of $\theta$ that result in a value of $h$ that is invertible, as per the requirements of the cryptosystem, we are left with a tiny amount. Simply enumerating all of these and performing the required encryption and decryption then gives us the flag.

For a better understanding of the math and the implementation in sage, we recommend going through Jack’s commented implementation below.

Originally, our idea for this challenge was to implement the entire cryptosystem, including generating the actual public key, but unfortunately, it became either very hard or very artificial to do this in a nice way. The public key generation is probably the hardest part of implementing this cryptosystem, and often requires a fair bit of fighting with sage and multivariate polynomial rings to get some semblance of “symbolic” computations.

Our experiments and implementaiton of this can be found in the github repository but are probably too big to include in this post.

Fun fact: there was an easter egg in the provided PDF file that hints at why the challenge is named the way it is. When you look at the metadata, you’ll find the following title:

MMO might actually just stand for massive multivariate output

Implementation

Here’s Jack’s fairly ugly playtest solution which, although not quite as beautiful as Robin’s, has some additional comments made throughout. Considering a big chunk of this challenge was learning how to correctly implement certain pieces of the paper, we hope this helps!

Think of this as a writeup of how the SageMath side of things worked, nested within the main write up!

def string_to_sage(maths):

"""

Reads a string from the output file and returns

a parsed sage interpretation of the string

"""

return eval(preparse(maths.strip()))

def file_to_sage(line_number, split_str):

"""

Reutrns a parsed string which can be manipulated by

SageMath given the line number of the file and where

to split the line.

"""

maths_string = data[line_number].split(split_str)[-1]

return string_to_sage(maths_string)

def from_V_to_bytes(V):

"""

Returns a bytes string from an element of \mathbb{V}

"""

bs = []

for x in V:

bs.append(x.integer_representation())

return bytes(bs)

def xor_bytes(b1, b2):

return bytes([a^^b for a,b in zip(b1,b2)])

# Read the file as lines (string)

with open('output.txt') as f:

data = f.readlines()

# Construct element x of field GF(2)

x = GF(2)['x'].gen()

# Use this to create F_2^8 with a basis element called alpha

# to match output.txt

modulus = x^8 + x^4 + x^3 + x^2 + 1

F.<alpha> = GF(2^8, name="alpha", modulus=modulus)

# Now lets make a polynomial ring with X as the generator

R.<X> = F['X']

# This polynomial is a mess, so we pull it from the file

# rather than paste it in

irr_poly = file_to_sage(3, ' 2^8 with modulus ')

# Finally, we get our extension field K by taking the quotient

# with our irreducible polynomial

K.<X> = R.quotient_ring(irr_poly)

n = irr_poly.degree()

assert n == 60 # match with statement in Section 4

"""

To solve this challenge, we need to take elements from output

and correctly perform encryption AND decryption. Lets start by

definining our functions.

The function phi, phi inverse can be computed from our basis

"""

beta = [X^i for i in range(n)]

"""

We will need this to add zeros as x.list() so it is length n.

x.list() only gives up to highest order (cuts off trailing 0)

Kinda annoying... If you know a better way, let us know!

"""

def pad_list_x(x):

return x.list() + [0]*(n - len(x.list()))

"""

Okay, now we can define phi and its inverse

"""

# phi: K -> V

def phi(x):

return vector(F, pad_list_x(x))

# phi^-1: V -> K

def phi_inv(a_vec):

return sum(a*b for a, b in zip(a_vec, beta))

"""

The function psi is just exponentiation, easy peasy to do this

in Sage. Note that later we pick h such that h_inv exists

"""

# psi: K -> K

def psi(u):

return u^h

# psi^-1: K -> K

def psi_inv(u):

return u^h_inv

"""

The L functions can be computed directly from M, k which

we are given in output.txt

"""

def L1(x):

return M1 * x + k1

def L1_inv(x):

return M1.inverse() * (x - k1)

def L2(x):

return M2 * x + k2

def L2_inv(x):

return M2.inverse() * (x - k2)

"""

Putting this all together we can write the excryption function

This is the function f given at the top of page 2

f: K -> K

"""

def encrypt(x):

tmp = L1(x)

tmp = phi_inv(tmp)

tmp = psi(tmp)

tmp = phi(tmp)

return L2(tmp)

"""

We're not given this, but simply performing the inverse of each

step backwards from encrypt() gives a valid decrypt function :)

"""

def decrypt(y):

tmp = L2_inv(y)

tmp = phi_inv(tmp)

tmp = psi_inv(tmp)

tmp = phi(tmp)

return L1_inv(tmp)

"""

Now all we have to do is extract the private key and flag

from the file and use our functions

Private key is made from (h, M1, k1, M2, k2). We are given

M1, M2, k1, k2 which we can extract from our data

"""

M1 = file_to_sage(66, 'M1: ')

M1 = Matrix(F, M1)

k1 = file_to_sage(67, 'k1: ')

k1 = vector(F, k1)

M2 = file_to_sage(69, 'M2: ')

M2 = Matrix(F, M2)

k2 = file_to_sage(70, 'k2: ')

k2 = vector(F, k2)

"""

The flag is split between two lines which are encrypted

and decrypted respectively. Lets grab the two pieces.

"""

flag_encrypted = file_to_sage(76, 'an encryption: ')

flag_encrypted = vector(F, flag_encrypted)

flag_decrypted = file_to_sage(77, 'a decryption: ')

flag_decrypted = vector(F, flag_decrypted)

"""

The final piece of the puzzle is to find \theta. We don't

know it, but we know there aren't that many options as we

need h_inv to exist. We can simply loop through and check

all valid theta.

"""

q = 2^8

for theta in range(2,n):

h = q^theta + 1

"""

h inverse must exist, so we must have that h is coprime

to the group order

"""

if gcd(h, q^n - 1) != 1:

continue

print(f'Guessing theta = {theta}')

h_inv = inverse_mod(h, q^n - 1)

k = decrypt(flag_encrypted)

k_xor_flag = encrypt(flag_decrypted)

k_bytes = from_V_to_bytes(k)

k_xor_flag_bytes = from_V_to_bytes(k_xor_flag)

print(xor_bytes(k_bytes, k_xor_flag_bytes))

# b'CHTB{Imai_and_Matsumoto_play_with_multivariate_cryptography}''

Flag

CHTB{Imai_and_Matsumoto_play_with_multivariate_cryptography}

Tetris 3D

Author: Robin

With all the timey-wimey weirdness going on, I have no idea if the aliens encrypted this before or after the tetris game. All I know is that I want my games back!

The flag consists entirely of uppercase characters, and is of the formCHTB{SOMETHINGHERE}. You’ll still have to insert the{}yourself.

Challenge

# The flag consists of only uppercase ascii letters

# You do have to fix up the flag format yourself

import string, hashlib, itertools

def clean(x):

return ''.join(c for c in x.upper() if c in string.ascii_letters)

def transpose(x, l):

return ''.join(x[i::l] for i in range(l))

def alphabet(r):

a = list(string.ascii_uppercase)

for i in range(len(a) - 1, 0, -1):

j = r.randrange(0, i)

a[i], a[j] = a[j], a[i]

return ''.join(a)

def encrypt(text, l, keys):

enc = ''.join(c.translate(k) for c, k in zip(text, itertools.cycle(keys)))

return transpose(enc, l)

class RNG:

A = 101565695086122187

C = 56502943171806276

M = 288230376151711717

def __init__(self, seed):

self.state = seed

def next(self):

self.state = ((self.state * self.A) + self.C) % self.M

return self.state

def randrange(self, low, high):

assert high > low

range = high - low

limit = range * (self.M // range)

while True:

res = self.next()

if res <= limit:

return (res % range) + low

if __name__ == "__main__":

with open("content.txt", "r") as f:

text = clean(f.read())

with open("flag.txt", "r") as f:

text += clean(f.read())

seed = int.from_bytes(hashlib.sha256(text.encode()).digest(), "big")

rng = RNG(seed)

L = rng.randrange(1, 20)

K = rng.randrange(1, 20)

print(f"{L = }")

print(f"{K = }")

keys = [''.maketrans(string.ascii_uppercase, alphabet(rng)) for _ in range(K)]

with open("content.enc.txt", "w") as f:

f.write(encrypt(text, L, keys))

Solution

Both the challenge, and the general approach to the solution will be similar to that of Tetris. The major difference this time: rather than a single monoalphabetic substitution, we now have a periodical polyalphabetic substitution with key length $K$.

Finding K and L

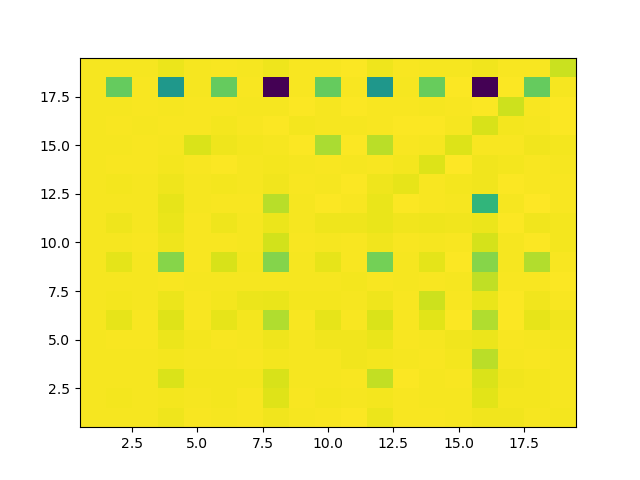

In contrast to what we did for Tetris, we won’t be using brute force to solve every possible combination of $K$ and $L$. Rather, we observe that due to the fact we no longer have a single monoalphabetic substitution, and a wrong guess for $K$ and/or $L$ mixing up different alphabet keys, we can now more accurately estimate if a guess is correct with the IoC again. When we plot the average distance from our reference IoC for every possible $K, L$ attempt, we can see some interesting results ($K$ is on the horizontal axis, $L$ on the vertical):

We can clearly see that we get the overall best results for $L = 18$, and two spikes for $K = 8$ and $K = 16$. Everyone knows of course that $16 = 2 \cdot 8$, and so that second spike is explained by the fact that a twofold repetition of a sequence of alphabet keys will be an equally valid solution. We however clearly should choose to solve for $K = 8$ as that will give us more data per key to work with, and cost less time overall.

Solving 8 repeating substitutions

After undoing the transposition by $L$, we are now left with a periodical polyalphabetic substitution, and we can try to attack it with a hill climbing approach again.

Our approach is similar to the technique set out in Slippery hill-climbing technique for ciphertext-only cryptanalysis of periodic polyalphabetic substitution ciphers by Thomas Kaeding. Our fitness score will be the same as before: a sum of log-space quadgram frequencies. Differently from before, we can’t solve a single substitution at once, as they can’t form proper (consecutive) quadgrams. Instead, we will score the entire plaintext, covering all keys at once.

We improve each single substitution individually, starting from a random key, while keeping the others fixed. If we repeat this process enough, to make sure our randomness did not accidentally miss an improvement, this will very frequently find the correct solution, without getting stuck in local optima.

This “reset” of a single substitution is what makes the hillclimbing slippery as in the title of the referenced paper. This form of optimization, where we find an optimum when changing a single part of the solution, while keeping everything else fixed, is commonly seen in other areas as well.

While it might also be possible to solve the substitutions with some more manual work after assigning the closest matching reference frequencies as initial keys and performing manual improvements and attempting some crib dragging, due to the sheer tedium involved, we did not attempt this ourselves.

Implementation

We take a two part implementation here, where the resource-intensive hill climbing iterations are done in C++ to have a quicker develop-test cycle, and a faster solution overall in the end. The initial data-analysis phase that allows us to determine $K$ and $L$ is implemented in python where we can (un)transpose more easily, and nicely visualize our search for the parameters.

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

from collections import Counter

import numpy as np

import string, hashlib, itertools, random, math

def clean(x):

return ''.join(c for c in x.upper() if c in string.ascii_letters)

def IoC(x):

num = sum(x * (x - 1) for _, x in Counter(x).most_common())

den = len(x) * (len(x) - 1)

return num / den

def untranspose(c, l):

n = len(c) // l

r = []

s = 0

for i in range(l):

t = n

if len(c) % l > i:

t = n + 1

r.append(c[s:s+t])

s += t

res = ''.join(''.join(p) for p in itertools.zip_longest(*r, fillvalue=''))

assert c == ''.join(res[i::l] for i in range(l))

return res

def quadgramstats(x):

c = Counter(x[i:i+4] for i in range(len(x) - 4))

return {k:math.log(v / len(x), 10) for k, v in c.most_common()}

def score(x):

return sum(targetQuad.get(x[i:i+4], -24) for i in range(len(x) - 4)) / (len(x) - 3)

def fullscore(x, keys):

return score(untranspose(''.join(x[i::len(keys)].translate(''.maketrans(string.ascii_uppercase, k)) for i, k in enumerate(keys)), len(keys)))

def swap(x, a, b):

assert a <= b

if a == b: return x

return x[:a] + x[b] + x[a+1:b] + x[a] + x[b+1:]

def shuffled(x):

x = list(x)

random.shuffle(x)

return ''.join(x)

def hillclimb(c, K):

keys = [shuffled(string.ascii_uppercase) for _ in range(K)]

outer = 0

best = float("-inf")

bestk = keys

while outer < 5000 * K * K // len(c):

print("iterate")

for i in range(K):

keys[i] = shuffled(string.ascii_uppercase)

target = fullscore(c, keys)

fails = 0

while fails < 1000:

b = random.randrange(1, 26)

a = random.randrange(1, 26)

t = keys[:i] + [swap(keys[i], min(a, b), max(a, b))] + keys[i+1:]

ts = fullscore(c, t)

if ts > target:

target = ts

fails = 0

keys = t

else:

fails += 1

if target > best:

best = target

bestk = keys

outer = 0

print("improved", target)

else:

outer += 1

return bestk

def transform(c, l, k):

ut = untranspose(c, l)

return sum(IoC(ut[i::k]) for i in range(k)) / k

reference = clean(open("atotc.txt", "r").read())

targetIoC = IoC(reference)

targetQuad = quadgramstats(reference)

ctxt = clean(open("content.enc.txt", "r").read())

x = np.arange(0.5, 20, 1)

y = np.arange(0.5, 20, 1)

z = np.array([[abs(targetIoC - transform(ctxt, i, j)) for j in range(1, 20)] for i in range(1, 20)])

plt.pcolormesh(x, y, z)

plt.show()

_, K, L = min((z[i - 1][j - 1], j, i) for i in range(1, 20) for j in range(1, 20))

print(f"{K = }")

print(f"{L = }")

ctxt = untranspose(ctxt, L)

with open("qgram.ref", "w") as o:

o.write(clean(reference))

with open("ctxt.tmp", "w") as o:

o.write(ctxt)

import os

os.system(f"clang++ -O3 -o hillclimber hillclimber.cpp && ./hillclimber qgram.ref ctxt.tmp {K}")

# keys = hillclimb(ctxt, K)

# print(keys)

# print(untranspose(''.join(ctxt[i::K].translate(''.maketrans(string.ascii_uppercase, keys[i])) for i in range(K)), K))

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

#include <random>

using namespace std;

inline int idx(char x) { return x - 'A'; }

inline int dec(string x) {

return 26*26*26*idx(x[0]) + 26*26*idx(x[1]) + 26*idx(x[2]) + idx(x[3]);

}

double qgrams[26*26*26*26];

void fillqgram(string x) {

for (int i = 0; i < 26*26*26*26; i++)

qgrams[i] = -1;

for (int i = 0; i < x.length() - 3; i++) {

qgrams[dec(x.substr(i, 4))]++;

}

for (int i = 0; i < 26*26*26*26; i++) {

if (qgrams[i] == -1) qgrams[i] = -24;

else qgrams[i] = log10((qgrams[i] + 1) / (x.length() - 3));

}

}

double score(string x) {

double res = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < x.length() - 3; i++) {

res += qgrams[dec(x.substr(i, 4))];

}

return res / (x.length() - 3);

}

string decrypt(string x, vector<string> keys) {

string res = x;

for (int i = 0; i < x.length(); i++) {

res[i] = keys[i%keys.size()][x[i] - 'A'];

}

return res;

}

string shuffled() {

string x = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ";

random_shuffle(x.begin(), x.end());

return x;

}

pair<string, vector<string>> hillclimb(string c, int K) {

vector<string> keys(K);

for (int i = 0; i < K; i++) keys[i] = shuffled();

int outer = 0;

double best = -numeric_limits<double>::infinity();

vector<string> bestk = keys;

while (outer < 5000 * K * K / c.length()) {

cout << "iterate" << endl;

for (int i = 0; i < K; i++) {

keys[i] = shuffled();

double target = score(decrypt(c, keys));

int fails = 0;

while (fails < 1000) {

int a = rand() % 26;

int b = rand() % 26;

swap(keys[i][a], keys[i][b]);

double ts = score(decrypt(c, keys));

if (ts > target) {

target = ts;

fails = 0;

} else {

swap(keys[i][a], keys[i][b]);

fails++;

}

}

if (target > best) {

best = target;

bestk = keys;

outer = 0;

cout << "improved " << best << endl;

} else {

outer++;

}

}

}

return {decrypt(c, bestk), bestk};

}

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

if (argc < 4) {

cerr << "Usage: hillclimber quadgram_reference.txt encrypted.txt keysize" << endl;

return 1;

}

{

ifstream qf(argv[1]);

stringstream qfref;

qfref << qf.rdbuf();

fillqgram(qfref.str());

}

int K = atoi(argv[3]);

ifstream cf(argv[2]);

stringstream cs;

cs << cf.rdbuf();

auto res = hillclimb(cs.str(), K);

cout << res.first << endl;

for (auto k : res.second) cout << k << endl;

}

Flag

CHTB{ALMOSTLIKEAVIGENERECIPHERBUTNOTQUITEORSLIDINGDOWNTHATHILL}

Hyper Metroid

Author: Jack

Dropping a morph ball bomb, Samus cracked open the floor and dropped down into the guts of Phaaze. At the end of the tunnel is a locked chest containing the hyper beam upgrade. Samus found the encrypted key preserved in a ball of glowing biomass, but can’t decode it. Help Samus capture the flag so she can eradicate the alien invasion once and for all.

Challenge

from secrets import flag

def alien_prime(a):

p = (a^5 - 1) // (a - 1)

assert is_prime(p)

return p

def encrypt_flag():

e = 2873198723981729878912739

Px = int.from_bytes(flag, 'big')

P = C.lift_x(Px)

JP = J(P)

return e * JP

def transmit_point(P):

mumford_x = P[0].list()

mumford_y = P[1].list()

return (mumford_x, mumford_y)

a = 1152921504606846997

alpha = 1532495540865888942099710761600010701873734514703868973

p = alien_prime(a)

FF = FiniteField(p)

R.<x> = PolynomialRing(FF)

h = 1

f = alpha*x^5

C = HyperellipticCurve(f,h,'u,v')

J = C.jacobian()

J = J(J.base_ring())

enc_flag = encrypt_flag()

print(f'Encrypted flag: {transmit_point(enc_flag)}')

Solution

Disclaimer

This discussion is going to be a mix of ways I think about these things, some terrible glossing over of details, and a general drive towards being able to go from maths equations to SageMath. I’m learning this topic as I make challenges like this, so if I’m wrong about anything please pull me up on it and help me be better!

This challenge is essentially the same as Super Metroid, where the solution of the puzzle requires computing the order of the group used to hide the flag. The difference here is that rather than an elliptic curve, the flag is encrypted as an element of the Jacobian of a hyperelliptic curve, for which there are no general algorithms which can compute the order of the Jacobian in a reasonable amount of time for the size of the primes we use.

Aside: Jacobian?? I thought we just did points on curves for crypto!

When we do ECC we think about points and we define a group operation on these points which is Abelian which allows us to do things like key-exchanges due to the assumed hardness of the discrete log problem. When we consider hyperelliptic curves, this group law is not defined for the points on the curve but rather specifc sums of points which we call divisors. The Jacobian is the quotient group of these divisors with the so-called principle divisors (I’m being vague on purpose here to keep word count down). For the case for genus-one curves, the Jacobian of the curve is isomorphic to the original curve! It turns out you’ve been doing working with Jacobians all along without realising. Now we’re generalising to hyerelliptic curves from ECC, we need to be more careful and make sure we’re working within the Jacobian.

The challenge is solved by using that we consider a very special class of hyperelliptic curve whose Jacobian is the quotient of the Jacobian of the famous Fermat curve $X^n + Y^n = 1$. The case for $n = 3$ was considered by Gauss and is one of the canonical examples when discussing point counting on elliptic curves.

In particular, this challenge is solvable because the prime we use in $F_p$ is a generalised Mersenne prime, for which there is a very efficient algorithm to compute the order of the Jacobian of the curve. This is the topic of this write-up.

The discussion we offer here follows Chapter 6 of Algebraic Aspects of Cryptography by Koblitz, which was the inspiration for this challenge.

In this discussion, we consider $n = 2g + 1$ to be an odd prime, with $g$ the genus of the hyperelliptic curve. The case of $g = 1$ is the special case of elliptic curves, where computing the order can be done with Schoofs algorithm. We will mention the $n = 3$ case again soon, referencing a result via Gauss which will help us double-check how we’re using SageMath.

Aside: Genus? I thought that had something to do with topology?

Most people come into contact with the notion of genus when they read about topology. A sphere has genus 0, a doughnut and a mug both have genus 1. As a physicist, I think about genus as counting the number of handles the “shape” has.

This intuition comes back when you consider hyperelliptic curves over $\mathbb{C}$. An elliptic curve can be thought of as a torus (🍩) and higher genus hyperelliptic curves as objects with more “holes” or “handles”. Anyway… back to the challenge.

Let us begin our discussion working with our hyperelliptic curve

\[C: v^2 + v = u^n\]with solutions over $\mathbb{F}_p$ for some large prime $p$. Cryptographically, we will consider the Jacobian $\mathbb{J}$ of this curve, which is where we will perform our group operations.

To solve this challenge, we need to know the order of the Jacobian of a particular curve so that we can find the multiplicative inverse of $e$. Before continuing, lets introduce a few more symbols we will need

- $\zeta = e^{2\pi i / n}$ is a nth root of unity and generator of the nth cyclotomic field: $\zeta^n = 1$.

- $\alpha \in \mathbb{F}_p$ is a non-nth power

- $\chi$ is a unique multiplicative map on $\mathbb{F}_p^{\star}$ such that $\chi(\alpha) = \zeta$

- $\sigma_i$ is an automorpishm (a symmetry) of the field $\mathbb{Q}(\zeta)$ such that $\sigma_i(\zeta) = \zeta^i$

With these pieces, we can write the Jacobi sum of the character $\chi$ with itself as

\[J(\chi, \chi) = \sum_{y \in \mathbb{F}\_p} \chi(y) \chi(1 - y)\]Woah!! Hang on!! This is a CTF not a maths lecture

- Don’t worry about $\chi$ if you don’t want, we wont need it to get the solve

- Read $\sigma_i(\zeta)$ simply as “take $\zeta$ to the ith power”

- We already have $\alpha$, so that’s just some number

Why do I care about Jacobi sums??? Give me the flag!!

Turns out, the Jacobi sum of this character $\chi$ is exactly what we want to solve this challenge. We will see that the form of the prime $p$ allows us to efficiently compute the value of $J(\chi,\chi)$ and hence solve the challenge via the following identities, quoted from the text without proof.

The number of points $M$ on the curve $C$ is equal to

\[M = p + 1 + \sum_{i = 1}^{n-1} \sigma_i(J(\chi,\chi))\]Futhermore, the number of points on the Jacobian (i.e. the solution to this puzzle) is given by a similar equation

\[N = \prod_{i = 1}^{n - 1} \sigma_i(J(\chi,\chi) + 1)\]Using the norm map (see our blog post from TetCTF2021 if you want to read more about the norm map) we can write this as

\[N = \mathbb{N} (J(\chi,\chi) + 1)\]Now we see if we can efficiently compute $J(\chi,\chi)$ then we can find the order of the curve and hence solve the challenge!

However, before diving into the Jacobi sum, let’s cover the final twist of the puzzle. We do not consider a curve $C$ as above, but instead a twist of the curve. For integers $i = 0,1$, and $j = 0,\ldots n-1$ valid twists of $C$ are given by:

\[C: v^2 + v + \frac{1}{4}(1 - \beta^i) = \beta^i \alpha^j u^n\]These twists are interesting to us, as we can perform the twists of various curves and compute the order of the Jacobian, looking for curves where this is (divisible by) a large prime, making it suitible for cryptography, in the same way that we look for elliptic curves with small cofactors to protect against an array of attacks.

Looking at our challenge source, we have $i = 0$, $j = 1$ such that the genus-2 curve is given by

\[C: v^2 + v = \alpha u^5.\]The general form for the order of the Jacobian of these twisted curves is given by

\[N_{i,j} = \mathbb{N} (J(\chi,\chi) + (-1)^i \zeta^j)\]and so in our particular example we wish to find

\[N_{0,1} = \mathbb{N} (J(\chi,\chi) + \zeta).\]Aside: Example using Elliptic Curves

Finding $J(\chi,\chi)$ for $n=3$ has a simple solution from a result of Gauss, who found a way to count the number of points on the curve

\[C: v^2 + v = u^3\]Let us use that:

- We have an integer $a$ such that $a^3 \equiv 1 \mod p$, $a \not\equiv 1 \mod p$.

- $\alpha$ will be a non-cube in $\mathbb{F}_p$

- $\zeta = \frac{1}{2}(-1 + \sqrt{-3})$

If you want to find $a$, we can simply take $\alpha^{(p-1)/3} \mod p$.

It turns out, the Jacobi sum in this case can be computed from

\[J(\chi, \chi) = \pm \zeta^k \gcd(p, a-\zeta)\]Where we consider these all as element in $\mathbb{Z}[\zeta]$. The root of unity $\pm\zeta^k$ is hand-picked such that $J(\chi, \chi) \equiv -1 \mod 3$ in $\mathbb{Z}[\zeta]$.

We mention this because it’s an excellent playground to learn how to define these objects in SageMath, where we can compare our solution with E.order() to make sure it’s all working!

p = 247481649253408897532555115418385747563

F = GF(p)

E = EllipticCurve(F, [0,0,1,0,0])

# Elliptic Curve defined by y^2 + y = x^3 over Finite Field of size 247481649253408897532555115418385747563

# Find an element of order 3

g = F.multiplicative_generator()

a = g^((p-1)/3)

assert a^3 == 1

# Define zeta

k = CyclotomicField(3)

zeta = k.gen()

# Define Euclidean Ring ZZ[zeta]

ER = QuadraticField(-3).ring_of_integers()

# Comute the Jacobi sum

zetak = -1

J = zetak*gcd(ER(p), ER(a) - ER(zeta))

# Note: we picked zetak such that

assert ER(J).mod(3) == ER(-1).mod(3)

# Compute order and check

N = norm(J + 1)

assert E.order() == N

This is very fast using only $O(\log^3 p)$ operations, compared to Schoof’s algorithm which is also fast: $O(\log^8 p)$ and works in a far more general setting.

It turns out, we picked a hyperelliptic curve where this treatment nicely generalises! Lucky you. We have that for $n = 2g + 1 \geq 5$, with our prime $p$ in the special form

\[p = \frac{a^n - 1}{a-1},\]we can apply a similar method to compute the Jacobi sum. A prime of this form is called a generalised Mersenne prime.

Referencing the text, the expression for $J(\chi, \chi)$ we want to compute is given by

\[J(\chi, \chi) = \pm \zeta^k \prod_{i=1}^g (a - \sigma_i^{-1} (\zeta)),\]where now we pick $\pm \zeta^k$ such that

\[J(\chi, \chi) \equiv -1 \mod (\zeta - 1)^2\]in the ring $\mathbb{Z}[\zeta]$.

In the text, it is explained that for $n=5$, we can just tabulate $\zeta^k$ choices by computing $a \mod 5$ using that

\[\zeta^j = (1 + \zeta - 1)^j \equiv 1 + j(\zeta - 1) \mod (\zeta - 1)^2\]| $a \mod 5$ | $\pm \zeta^k$ |

|---|---|

| 0 | $-\zeta$ |

| 2 | $-\zeta^4$ |

| 3 | $\zeta^2$ |

| 4 | $\zeta^3$ |

However there are so few options, we could simply enumerate them in a loop and stop when we obey our congruence

n = 5

g = 2

k = CyclotomicField(n)

ER = QuadraticField(-n).ring_of_integers()

zeta = k.gen()

for i in range(2):

for j in range(n):

zetak = (-1)^i * (zeta)^n

J = zetak * prod([ (k(a) - zeta^(1/l) ) for l in range(1,g+1)])

if ER(J).mod((zeta - 1)^2) == ER(-1).mod((zeta - 1)^2):

print(i,j)

exit()

All that’s left is to take the work from the earlier example and the details from our elliptic curve example and put it into SageMath!

Implementation

def data_to_jacobian(data):

xs, ys = data

pt_x = R(list(map(FF, xs)))

pt_y = R(list(map(FF, ys)))

pt = (pt_x, pt_y)

return J(pt)

def alien_prime(a):

p = (a^5 - 1) // (a - 1)

assert is_prime(p)

return p

def find_order(a,i,j):

g = 2

n = 5

p = (a^n - 1) // (a - 1)

k = CyclotomicField(n)

zeta = k.gen()

r = a % 5

if r == 0:

zetak = -zeta

elif r == 2:

zetak = -zeta^4

elif r == 3:

zetak = zeta^2

elif r == 4:

zetak = zeta^3

J = zetak * prod([ (k(a) - zeta^(1/l) ) for l in range(1,g+1)])

N = norm(J + (-1)^i * zeta^j)

return N

a = 1152921504606846997

p = alien_prime(a)

alpha = 1532495540865888942099710761600010701873734514703868973

FF = FiniteField(p)

R.<x> = PolynomialRing(FF)

h = 1

f = alpha*x^5

C = HyperellipticCurve(f,h,'u,v')

J = C.jacobian()

J = J(J.base_ring())

enc_flag = ([1276176453394706789434191960452761709509855370032312388696448886635083641, 989985690717445420998028698274140944147124715646744049560278470410306181, 1], [617662980003970124116899302233508481684830798429115930236899695789143420, 429111447857534151381555500502858912072308212835753316491912322925110307])

JQ = data_to_jacobian(enc_flag)

order = find_order(a, 0, 1)

e = 2873198723981729878912739

d = inverse_mod(e, order)

rec_JP = d*JQ

rec_x = rec_JP[0].roots()[0][0]

print(int(rec_x).to_bytes(28, 'big'))

#b'CHTB{hyp3r_sp33d_c0unting!!}'

Flag

CHTB{hyp3r_sp33d_c0unting!!}

SpongeBob SquarePants: Battle for Bikini Bottom – Rehydrated

Author: Robin

Wait,

spongebobandsquarepantsdon’t hash to the same thing?

Challenge

PBOXES = [[4, 0, 3, 2, 6, 8, 1, 13, 16, 7, 15, 12, 11, 9, 14, 10, 17, 5], [6, 13, 17, 8, 7, 11, 15, 5, 0, 10, 4, 16, 1, 3, 14, 12, 9, 2], [9, 17, 13, 11, 4, 10, 16, 8, 14, 7, 15, 1, 6, 5, 12, 3, 0, 2], [3, 14, 17, 5, 11, 2, 10, 12, 1, 16, 6, 9, 0, 4, 8, 15, 13, 7], [6, 9, 11, 16, 8, 10, 7, 14, 15, 12, 5, 1, 4, 0, 3, 17, 13, 2], [0, 13, 9, 6, 2, 15, 5, 11, 17, 14, 12, 16, 7, 3, 10, 4, 1, 8], [7, 0, 8, 13, 16, 1, 15, 17, 5, 14, 10, 3, 2, 12, 9, 4, 6, 11], [10, 4, 17, 7, 2, 1, 11, 13, 5, 6, 16, 8, 9, 0, 12, 3, 15, 14]]

SBOX = [74, 3, 10, 192, 95, 220, 206, 247, 200, 66, 139, 64, 39, 5, 62, 207, 63, 81, 120, 30, 55, 121, 219, 107, 45, 156, 237, 211, 190, 125, 35, 162, 248, 216, 20, 26, 166, 80, 122, 37, 254, 177, 225, 14, 33, 76, 181, 227, 168, 51, 161, 218, 41, 18, 209, 71, 236, 25, 150, 241, 228, 119, 97, 85, 129, 194, 130, 195, 210, 123, 22, 102, 65, 203, 193, 128, 132, 144, 253, 134, 124, 48, 141, 54, 60, 224, 226, 246, 19, 148, 29, 91, 173, 243, 244, 88, 208, 7, 198, 103, 217, 43, 199, 24, 58, 160, 221, 151, 89, 214, 69, 82, 112, 115, 127, 155, 99, 180, 164, 172, 27, 109, 21, 185, 187, 145, 140, 96, 201, 137, 138, 0, 6, 142, 34, 251, 8, 72, 11, 75, 205, 70, 57, 174, 184, 204, 149, 163, 111, 59, 186, 79, 53, 42, 52, 110, 189, 104, 15, 196, 4, 188, 117, 36, 158, 197, 78, 61, 154, 242, 231, 223, 32, 17, 183, 56, 143, 233, 16, 169, 165, 245, 23, 101, 116, 38, 84, 135, 234, 133, 147, 46, 131, 67, 2, 136, 50, 167, 86, 118, 1, 9, 202, 73, 12, 191, 235, 153, 152, 238, 213, 222, 68, 28, 239, 93, 215, 176, 98, 126, 159, 13, 250, 94, 87, 113, 49, 31, 83, 232, 229, 108, 240, 170, 175, 100, 44, 230, 255, 114, 249, 40, 178, 47, 77, 252, 105, 179, 146, 182, 171, 157, 212, 106, 92, 90]

BLOCKSIZE = 8

def blocks(x):

return list(zip(*[iter(x)] * BLOCKSIZE))

def permute(s):

res = [0 for _ in s]

for b in range(8):

for i, x in enumerate(s):

res[PBOXES[b][i]] |= (x & (1 << b))

return res

def H(m):

assert len(m) % BLOCKSIZE == 0

state = [0 for _ in range(18)]

for b in blocks(m):

for i, c in enumerate(b):

state[i] ^= c

for _ in range(8):

state = permute(state)

state = [SBOX[b] for b in state]

return bytes(state)

if __name__ == "__main__":

import os

os.chdir(os.path.abspath(os.path.dirname(__file__)))

print("Who lives in a pineapple under the sea?")

a = bytes.fromhex(input("> ").strip())

b = bytes.fromhex(input("> ").strip())

assert a != b

assert H(a) == H(b)

with open("flag.txt") as f:

print(f.read())

And the fixed version that does not suffer from the unintended solution:

PBOXES = [[4, 0, 3, 2, 6, 8, 1, 13, 16, 7, 15, 12, 11, 9, 14, 10, 17, 5], [6, 13, 17, 8, 7, 11, 15, 5, 0, 10, 4, 16, 1, 3, 14, 12, 9, 2], [9, 17, 13, 11, 4, 10, 16, 8, 14, 7, 15, 1, 6, 5, 12, 3, 0, 2], [3, 14, 17, 5, 11, 2, 10, 12, 1, 16, 6, 9, 0, 4, 8, 15, 13, 7], [6, 9, 11, 16, 8, 10, 7, 14, 15, 12, 5, 1, 4, 0, 3, 17, 13, 2], [0, 13, 9, 6, 2, 15, 5, 11, 17, 14, 12, 16, 7, 3, 10, 4, 1, 8], [7, 0, 8, 13, 16, 1, 15, 17, 5, 14, 10, 3, 2, 12, 9, 4, 6, 11], [10, 4, 17, 7, 2, 1, 11, 13, 5, 6, 16, 8, 9, 0, 12, 3, 15, 14]]

SBOX = [74, 3, 10, 192, 95, 220, 206, 247, 200, 66, 139, 64, 39, 5, 62, 207, 63, 81, 120, 30, 55, 121, 219, 107, 45, 156, 237, 211, 190, 125, 35, 162, 248, 216, 20, 26, 166, 80, 122, 37, 254, 177, 225, 14, 33, 76, 181, 227, 168, 51, 161, 218, 41, 18, 209, 71, 236, 25, 150, 241, 228, 119, 97, 85, 129, 194, 130, 195, 210, 123, 22, 102, 65, 203, 193, 128, 132, 144, 253, 134, 124, 48, 141, 54, 60, 224, 226, 246, 19, 148, 29, 91, 173, 243, 244, 88, 208, 7, 198, 103, 217, 43, 199, 24, 58, 160, 221, 151, 89, 214, 69, 82, 112, 115, 127, 155, 99, 180, 164, 172, 27, 109, 21, 185, 187, 145, 140, 96, 201, 137, 138, 0, 6, 142, 34, 251, 8, 72, 11, 75, 205, 70, 57, 174, 184, 204, 149, 163, 111, 59, 186, 79, 53, 42, 52, 110, 189, 104, 15, 196, 4, 188, 117, 36, 158, 197, 78, 61, 154, 242, 231, 223, 32, 17, 183, 56, 143, 233, 16, 169, 165, 245, 23, 101, 116, 38, 84, 135, 234, 133, 147, 46, 131, 67, 2, 136, 50, 167, 86, 118, 1, 9, 202, 73, 12, 191, 235, 153, 152, 238, 213, 222, 68, 28, 239, 93, 215, 176, 98, 126, 159, 13, 250, 94, 87, 113, 49, 31, 83, 232, 229, 108, 240, 170, 175, 100, 44, 230, 255, 114, 249, 40, 178, 47, 77, 252, 105, 179, 146, 182, 171, 157, 212, 106, 92, 90]

INIT = [248, 142, 163, 165, 248, 3, 71, 246, 9, 67, 203, 73, 195, 2, 192, 201, 203, 136]

BLOCKSIZE = 8

def blocks(x):

return list(zip(*[iter(x)] * BLOCKSIZE))

def permute(s):

res = [0 for _ in s]

for b in range(8):

for i, x in enumerate(s):

res[PBOXES[b][i]] |= (x & (1 << b))

return res

def H(m):

assert len(m) % BLOCKSIZE == 0

state = INIT[:]

for b in blocks(m):

for i, c in enumerate(b):

state[i] ^= c

for _ in range(8):

state = permute(state)

state = [SBOX[b] for b in state]

return bytes(state)

if __name__ == "__main__":

import os

os.chdir(os.path.abspath(os.path.dirname(__file__)))

print("Who lives in a pineapple under the sea?")

a = bytes.fromhex(input("> ").strip())

b = bytes.fromhex(input("> ").strip())

assert a != b

assert H(a) == H(b)

with open("flag.txt") as f:

print(f.read())

Solution

Note: this challenge had a very significant unintended solution, which we will present first. If you don’t want a spoiler for the intended solution, make sure not to read too far ahead. Thanks to Mystiz for alerting me early on about the unintended solution, unfortunately we could not release the fixed version as an extra challenge during the contest itself

The hash function

Inspecting the source code given, we see a sponge function used as a hash function. Our goal is to create a collision for it, and obtain the flag.

The sponge does the following for each block of the message:

- Apply a bitwise xor between the bitrate of the state and the message

- For 8 rounds:

- Permute the bits of the entire state, each bit stays at the same “bit index”, but the bytes to which they belong are permuted

- Perform a substitution step for every byte of the state

The final state is then the hash value.

The easy approach

Since the permutations keep bits in the same bit position, any state of the form xx...x will remain the same under permutation.

We can simply feed enough 0 blocks so that we end up at the same point in the cycle containing 0 in the sbox. This gives us that "000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000" and "" do end up hashing to the same thing.

Clearly, this could not be the intended solution for a 4⭐ challenge… Quoting a certain discord user from the cryptohack discord I talked to:

yeah tbh I just started to try random stuff and it was just luck that it happened to work

NOTE: be aware that the originally intended solution will be described from this point on.

The actual solution

First, observe that finding two messages that collide in the capacity allows us to find two fully colliding messages by appending just a single block to each. Since the capacity is the same for both after the first blocks, we simply append two blocks that xor to the difference between the two bitrates at that point, and since a block is only mixed in once, that means that the final states will still entirely match.

Since the capacity of the sponge consists of 10 bytes, we expect to need about $2^{40}$ hashes to have a birthday attack on the collision. This might be feasible within the time limits, but even a small mess up or a lack of memory will easily lead to a failure here.

Instead, we can figure out that the construction is backdoored, by starting to ask ourselves the question “why are bits only permuted at a fixed index”. From there, if we further investigate the SBOX (and we can for example inspect the cycle decomposition of this permutation), we can discover the horrible secret: if the bits at index 2, 4, and 5 are all 0, they remain that way. These bits then further remain invariant after permutation too, as they remain at the same index.

So, if we ensure that the bits 2, 4, and 5 will always remain 0, in this case by making sure our message blocks also have 0s at those indices, we have reduced the security of this hash function from $\frac{10\cdot8}{2} = 40$ bits to $\frac{10\cdot 5}{2} = 25$ bits only. This brings it well in range of a birthday attack. Finally, the initial state has the correct bits fixed in the capacity, but not so in the bitrate. Therefore, we also introduce a first block that will map the bitrate part to have the wanted fixed bits too.

Implementing this in plain python will be very slow, but already running it in pypy instead will provide a significant speedup. It should also be possible to implement it in a compiled language for potentially even greater speeds.

Given that very little attention was spend on other properties of the SBOX or the permutation, other than fixing the backdoored bits, we suspect it might very well also vulnerable to some form of linear or differential cryptanalysis, and if so, we’d of course be interested in reading any other writeups covering that.

Implementation

The first loop in collide can be chosen to have a larger or smaller upper bound, in order to make a tradeoff between execution time and memory usage.

import random, tqdm

PBOXES = [[4, 0, 3, 2, 6, 8, 1, 13, 16, 7, 15, 12, 11, 9, 14, 10, 17, 5], [6, 13, 17, 8, 7, 11, 15, 5, 0, 10, 4, 16, 1, 3, 14, 12, 9, 2], [9, 17, 13, 11, 4, 10, 16, 8, 14, 7, 15, 1, 6, 5, 12, 3, 0, 2], [3, 14, 17, 5, 11, 2, 10, 12, 1, 16, 6, 9, 0, 4, 8, 15, 13, 7], [6, 9, 11, 16, 8, 10, 7, 14, 15, 12, 5, 1, 4, 0, 3, 17, 13, 2], [0, 13, 9, 6, 2, 15, 5, 11, 17, 14, 12, 16, 7, 3, 10, 4, 1, 8], [7, 0, 8, 13, 16, 1, 15, 17, 5, 14, 10, 3, 2, 12, 9, 4, 6, 11], [10, 4, 17, 7, 2, 1, 11, 13, 5, 6, 16, 8, 9, 0, 12, 3, 15, 14]]

SBOX = [74, 3, 10, 192, 95, 220, 206, 247, 200, 66, 139, 64, 39, 5, 62, 207, 63, 81, 120, 30, 55, 121, 219, 107, 45, 156, 237, 211, 190, 125, 35, 162, 248, 216, 20, 26, 166, 80, 122, 37, 254, 177, 225, 14, 33, 76, 181, 227, 168, 51, 161, 218, 41, 18, 209, 71, 236, 25, 150, 241, 228, 119, 97, 85, 129, 194, 130, 195, 210, 123, 22, 102, 65, 203, 193, 128, 132, 144, 253, 134, 124, 48, 141, 54, 60, 224, 226, 246, 19, 148, 29, 91, 173, 243, 244, 88, 208, 7, 198, 103, 217, 43, 199, 24, 58, 160, 221, 151, 89, 214, 69, 82, 112, 115, 127, 155, 99, 180, 164, 172, 27, 109, 21, 185, 187, 145, 140, 96, 201, 137, 138, 0, 6, 142, 34, 251, 8, 72, 11, 75, 205, 70, 57, 174, 184, 204, 149, 163, 111, 59, 186, 79, 53, 42, 52, 110, 189, 104, 15, 196, 4, 188, 117, 36, 158, 197, 78, 61, 154, 242, 231, 223, 32, 17, 183, 56, 143, 233, 16, 169, 165, 245, 23, 101, 116, 38, 84, 135, 234, 133, 147, 46, 131, 67, 2, 136, 50, 167, 86, 118, 1, 9, 202, 73, 12, 191, 235, 153, 152, 238, 213, 222, 68, 28, 239, 93, 215, 176, 98, 126, 159, 13, 250, 94, 87, 113, 49, 31, 83, 232, 229, 108, 240, 170, 175, 100, 44, 230, 255, 114, 249, 40, 178, 47, 77, 252, 105, 179, 146, 182, 171, 157, 212, 106, 92, 90]

BLOCKSIZE = 8

def blocks(x):

return list(zip(*[iter(x)] * BLOCKSIZE))

def permute(s):

res = [0 for _ in s]

for b in range(8):

for i, x in enumerate(s):

res[PBOXES[b][i]] |= (x & (1 << b))

return res

def H(m):

assert len(m) % BLOCKSIZE == 0

state = [0 for _ in range(18)]

for b in blocks(m):

for i, c in enumerate(b):

state[i] ^= c

for _ in range(8):

state = permute(state)

state = [SBOX[b] for b in state]

return bytes(state)

def collide():

s = {}

MASK = ~((1<<2)|(1<<4)|(1<<5))

for _ in tqdm.trange(2**25):

m = bytes(random.randrange(256) & MASK for _ in range(BLOCKSIZE * 3))

h = H(m)[BLOCKSIZE:]

if h in s and m != s[h]:

return s[h], m

s[h] = m

while True:

m = bytes(random.randrange(256) & MASK for _ in range(BLOCKSIZE * 3))

h = H(m)[BLOCKSIZE:]

if h in s and m != s[h]:

return s[h], m

print(len(s))

def xor(a, b):

return bytes(x ^ y for x, y in zip(a, b))

a, b = collide()

h1 = H(a)

h2 = H(b)

assert h1[BLOCKSIZE:] == h2[BLOCKSIZE:]

x1 = b"\0" * BLOCKSIZE

x2 = xor(h1[:BLOCKSIZE], h2[:BLOCKSIZE])

print(f"a = {(a + x1).hex()}")

print(f"b = {(b + x2).hex()}")

Flag

CHTB{b1tw1s3_backd00rs_d0n't_forg3t_to_w4sh_the1r_h4nds}