Side Channels: Remote Lab and Glitching AES Ledger Donjon CTF Writeup

These two challenges were part of the side channels category of Ledger Donjon CTF, and involved exploiting fault attacks. Writeups by joachim and esrever respectively.

Remote Lab (200pts)

A remotely accessible lab is testing a chip with fault injection. Can you extract the secret? http://remote-lab.donjon-ctf.io:9000

We were given a README file which tells us a bit more about the setup. This also included a snippet of the source code which is run on the chip:

uint32_t verify_password(const uint8_t * password, size_t len) {

uint8_t swap[16] = {0};

uint8_t tmp[16] = {0};

uint32_t res = 0;

size_t nlen = 16;

if (len<nlen) {

nlen = len;

}

// Speck endianness swap

for(int i=0;i<nlen;i++) {

swap[i] = password[i];

}

for(int i=0;i<16;i++) {

tmp[i] = swap[15-i];

}

speck_128_128_encrypt((uint64_t*)tmp, (uint64_t*)tmp, KEY);

for (uint32_t i=0; i<16; i++) {

res |= tmp[i] - ((uint8_t *)ENCRYPTED_PASSWORD)[i];

}

return (res | -res)>>31;

}

In addition to the README file, we were also given a remote_lab_client.py file with code to connect to the remote chip.

import numpy as np

import requests

from binascii import hexlify

url = 'http://remote-lab.donjon-ctf.io:9000'

def send_decrypt(data):

decrypt_cmd = {'cmd' : 'decrypt', 'data' : data }

x = requests.post(url, json = decrypt_cmd)

if x.headers["content-type"] == "application/octet-stream":

return x.content

else:

return x.json()

def send_verify(offset, password):

verify_pwd_cmd = {'cmd' : 'verify', 'offset' : offset, 'password': password }

x = requests.post(url, json = verify_pwd_cmd)

if x.headers["content-type"] == "application/octet-stream":

trace = np.frombuffer(x.content, dtype=np.float32)

return trace

else:

return x.json()

if __name__ == "__main__":

print(send_verify(666, "aa"*7))

print(send_decrypt("aa"*7))

From this information, we know a couple of things:

- We can decrypt any arbitrary data using the

decryptcommand. - We can analyze the power trace of the execution of the above C code with any arbitrary input password.

- Presumably we have to decrypt the encrypted password

ENCRYPTED_PASSWORDto recover the flag.

Because we have access to a decryption command, the hard part is recovering the encrypted password. If we look at the code above, we can see the ENCRYPTED_PASSWORD constant is compared with the encryption of the input password, byte by byte. Because we were not experienced at all with side-channels, our first idea was to find a plaintext which encrypts to all zeros. After all, if the ciphertext is all zeros, the power trace of the comparison might give use some useful information (as opposed to any arbitrary ciphertext).

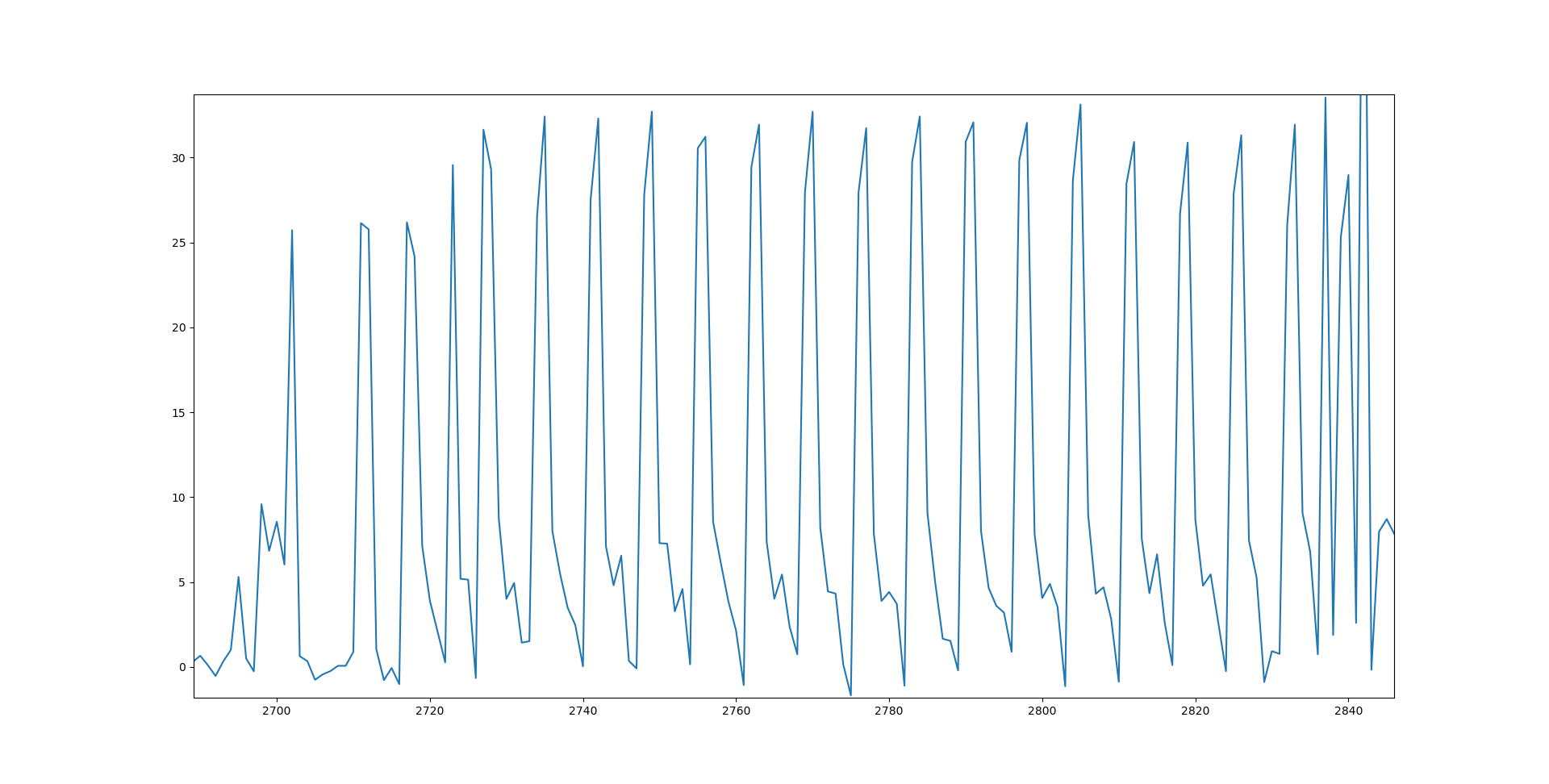

Luckily we have access to the decryption command, so obtaining this plaintext is easy: 2211932b3fba80c256e7af3ebff44beb will encrypt to the all zero ciphertext. We plotted this using MatPlotLib and got the following trace:

There’s at least 16 spikes here, so presumably the majority of them correspond to the subtraction of the ciphertext and ENCRYPTED_PASSWORD bytes. To confirm this hypothesis, we created 256 plaintexts which correspond to the all zero ciphertext, except with the byte at position 3 in the ciphertext variable.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

ct = bytearray(16)

for j in range(256):

ct[3] = j

pt = send_decrypt(ct.hex())

trace = send_verify(0, pt.hex())

plt.plot(trace)

plt.show()

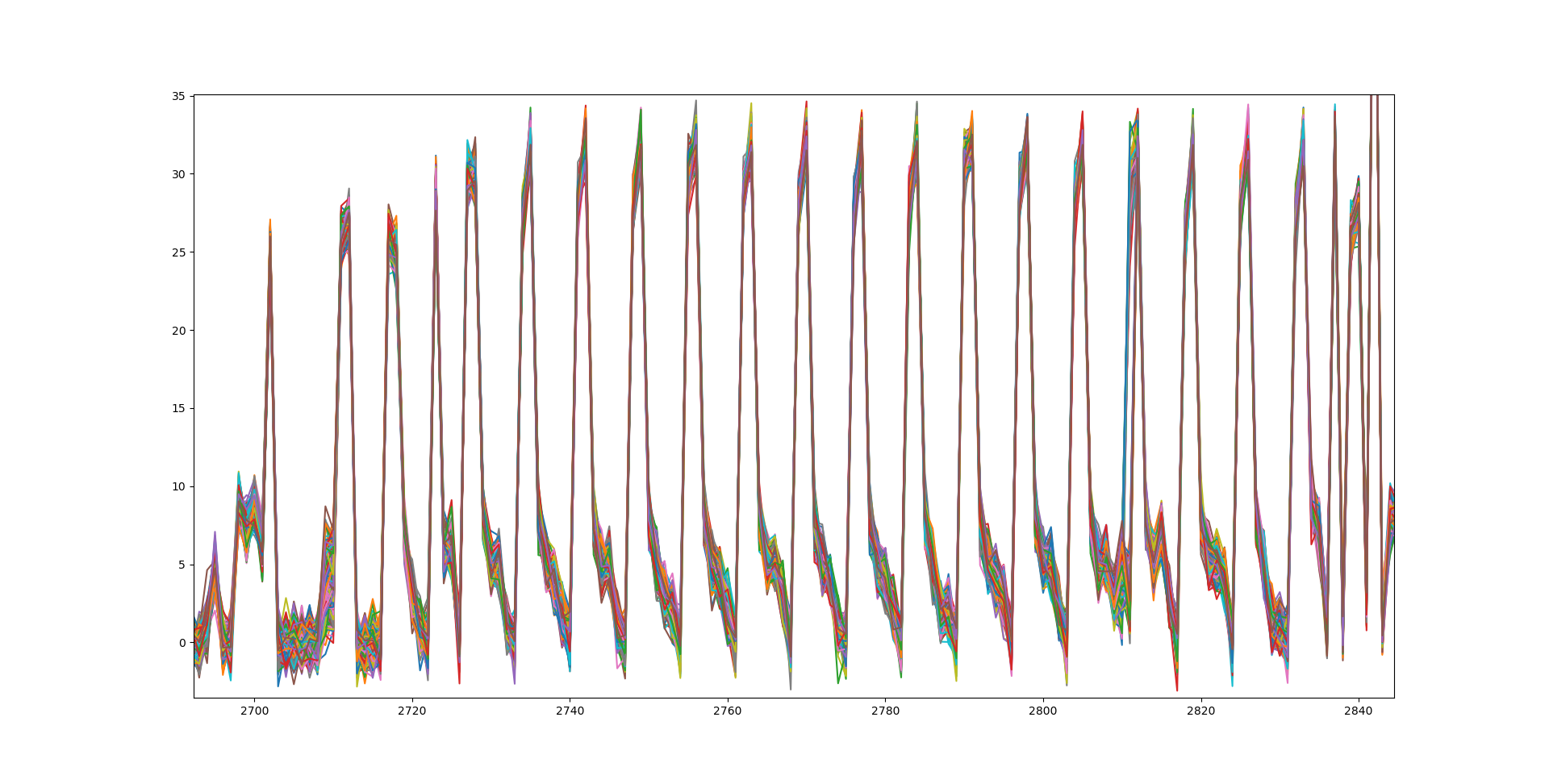

This time we recovered 256 traces and overlaid them in a graph using MatPlotLib:

One of the spikes looks messier than the other ones. This must be the spike corresponding to index 3 in the ciphertext. Let’s zoom in a bit more:

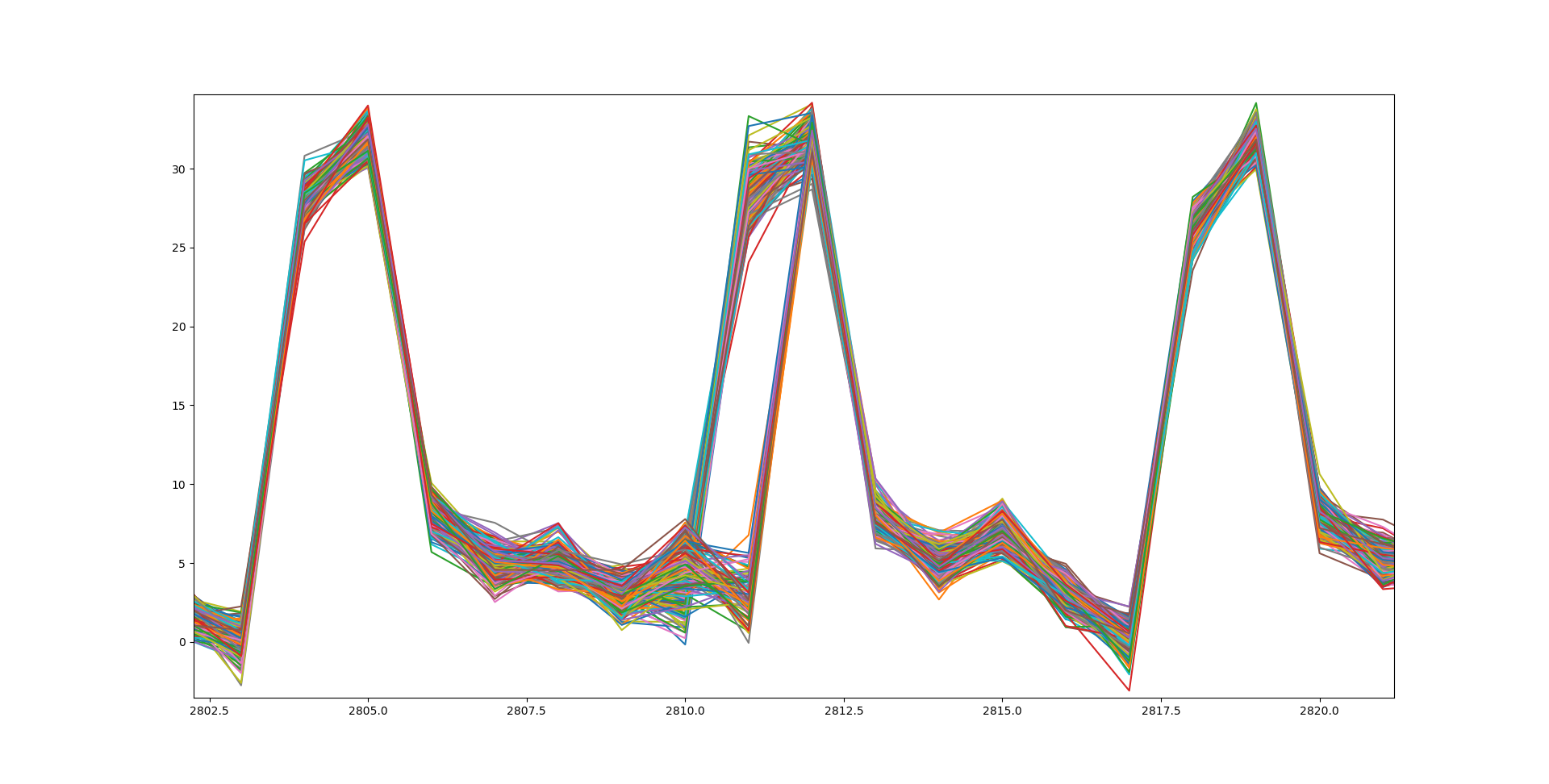

Interestingly, there’s two groups of traces when the power usage increases for the subtraction. For one of the groups, the power usage starts rising at index 2810 and peaks at 2811, while the other group starts at 2811 and ends at 2812. This is quite weird, and the size of the groups isn’t equal either. Somehow there is a bias, perhaps this leaks information about ENCRYPTED_PASSWORD?

Let’s try to print the trace index 2811 for each of the byte values at position 3 in the ciphertext.

ct = bytearray(16)

for j in range(256):

ct[3] = j

pt = send_decrypt(ct.hex())

trace = send_verify(0, pt.hex())

print(f"{j} has value {trace[2811]} at position 2811")

0 has value 28.836223602294922 at position 2811

1 has value 28.642549514770508 at position 2811

2 has value 27.260276794433594 at position 2811

3 has value 27.808557510375977 at position 2811

...

168 has value 31.61036491394043 at position 2811

169 has value 30.665077209472656 at position 2811

170 has value 31.924991607666016 at position 2811

171 has value 0.5633623003959656 at position 2811

172 has value 1.6181801557540894 at position 2811

173 has value 2.3114688396453857 at position 2811

...

253 has value 2.9744656085968018 at position 2811

254 has value 3.600590944290161 at position 2811

255 has value 2.384697914123535 at position 2811

The switch happens at byte values 171 at position 3 in the ciphertext: all byte values lower than 171 use more power, the others use less power. How could this happen? Looking back at the C code above, the byte by byte subtraction becomes very suspicious. The usual way to do this comparison would be using a xor operation.

Indeed, this choice is the key to the solution: when the byte at position 3 in the ciphertext is less than 171, the result of the subtraction becomes negative, thus increasing the power usage. This means that the byte at position 3 in ENCRYPTED_PASSWORD must be 171!

We can expand on this idea to recover the bytes in ENCRYPTED_PASSWORD one by one by simply generating 256 traces for each position and finding the cut off point. To speed up this process we used multithreading, one thread per position. Alternatively, one could use binary search to improve the performance even more.

def get_pos(i):

print(f"Guessing pos {i}")

ct = bytearray(16)

for j in range(256):

ct[i] = j

pt = send_decrypt(ct.hex())

trace = send_verify(0, pt.hex())

if trace[2832 - 7 * i] < 10:

print(f"Found {j} for pos {i}")

break

from multiprocessing import Pool

with Pool(16) as p:

p.map(get_pos, list(range(16)))

This results in the encrypted password, [32, 143, 191, 171, 171, 113, 9, 86, 114, 167, 105, 81, 91, 202, 230, 11].

Decrypting this using the decryption command gives the flag:

CTF{un1k0rnz_yo}

Glitching AES (300pts)

The challenge

I am targeting a board which runs an AES. That’s the perfect target to test my brand new glitcher! I did a lot of acquisitions, and a lot of glitching!

The results of my campaign are in this file.

Could you help me retrieve the secret key?

Decrypt the following message, in ECB mode, with the secret key to get the flag:

2801dd800e7ae333258224d5cbfc5420ec72a12256bdff61814972c7f93948f8

We are given a huge text file with each line having a (badly formatted) named tuple. The data looks like this after parsing into JSON.

{

"plaintext": [39, 249, 70, 194, 226, 136, 58, 125, 177, 143, 48, 239, 64, 93, 131, 84],

"time": 0,

"power": 3.9,

"result": "NO ANSWER"

}

{

"plaintext": [39, 249, 70, 194, 226, 136, 58, 125, 177, 143, 48, 239, 64, 93, 131, 84],

"time": 1,

"power": 1.53,

"result": [85, 230, 171, 32, 198, 36, 250, 207, 130, 251, 53, 53, 125, 242, 88, 143]

}

It is not quite clear what those fields mean, so we ask for clarification:

The idea is that a different power pulse/supply/whatever you wish to call it is applied to the device at each encryption. You then find the plaintext that was given as input, the value of this power, the time index when this pulse/supply/glitch was induced, and, finally, the obtained ciphertext. Sometimes however, the device does not answer (most likely due to this fault injection).

Investigation

The power of the glitches appear to be random. The time of the glitches ranges from 0 to 1624, each appears 2560 times and is applied to the same set of plaintexts. The result is either NO ANSWER or the correct output, no faulty output.

We first notice a correlation between power and result. If the power is less than 1, we always get an output; if the power is greater than 3, we always get NO ANSWER; the result can be either when the power is in between. Our interpretation is that we get NO ANSWER when the sum of glitch power and AES power consumption is larger than a threshold. In other words, we have partial information of the power consumption for each plaintext at each time indices.

At most of the time indices, there are about 1500 ~ 1700 NO ANSWER out of 2560 plaintexts input. However, there are only ~ 1000 NO ANSWER at some 121 time indices. This is probably because the power consumption is lower at those indices, so the total power is less likely to go over failing threshold after a glitch is applied.

The distribution of those 121 indices is very regular. Starting from index 116, there are clearly 13 clusters with an interval 121 between each other. Each cluster consists of three small segments of length 2, 5, 2, respectively. Here are the first two and the last clusters along with a partial cluster before index 116. The count goes as 4 + 13 * (2 + 5 + 2) = 121.

16, 17, 34, 35,

116, 117, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 155, 156,

237, 238, 255, 256, 257, 258, 259, 276, 277,

...

1568, 1569, 1586, 1587, 1588, 1589, 1590, 1607, 1608

At those time indices, result depends completely on the applied glitch power as if the power consumption is constant, so we guess that there is no operation happening at those time. Moreover, the interval between those indices are multiple of 16, suggesting that each time index corresponds to an operation on one byte.

We use differential power analysis to figure out what are the operations at some time indices. In particular, we first guess what happens at a specific time and compute the value. Then we split the data into two groups based on one bit of the value, say the lowest bit. (This is the so called selection function.)

The expected Hamming weight, hence power consumption, of values in group 0 is less than that in group 1, so we expect less frequent NO ANSWER in group 0. The difference will be significant if the guess is correct, and looks like random noise otherwise. It turns out that the values at time indices 1609 ~ 1624 are the final output, i.e. ciphertext. Operations at other time indices are listed below:

| Time indices | Operation |

|---|---|

| 0 ~ 15 | Initial AddRoundKey |

| 18 ~ 33 | Round 1 SubBytes |

| 100 ~ 115 | Round 1 MixColumns |

| 118 ~ 133 | Round 1 AddRoundKey |

| 139 ~ 154 | Round 2 SubBytes |

Now, it is clear that the 13 clusters of 5 no-operation indices are between rounds. This means that there are 14 rounds, hence we are dealing with AES-256.

The reliable selection functions in each byte are the fourth, the seventh, and the eighth lowest bit. It is not enough to recover the whole byte, however, using the fourth bit of SubBytes is enough to recover the round key in the previous AddRoundKey. We get the first half of the key from round 1 SubBytes, and the second half from round 2 SubBytes, and finally decrypt the flag.

Solution

def get_byte(byte_idx, results):

for byte_val in range(256):

group = lambda r: (sbox[r['plaintext'][byte_idx] ^ byte_val] >> 3) & 1

cnt0 = sum(map(lambda r: bool(r['result']) and not group(r), results))

cnt1 = sum(map(lambda r: bool(r['result']) and group(r), results))

if abs(cnt0 - cnt1) > 150:

return byte_val

key0 = bytearray(16)

for byte_idx in range(16):

results = get_results_at_time(18 + byte_idx)

key0[byte_idx] = get_byte(byte_idx, results)

print('key0:', key0)

# key0 = b'KYc\x15\xd2\x1d\xf5\xa51\x07\x9c\x83\x8e\x11\xee\xe6'

key1 = bytearray(16)

for byte_idx in range(16):

results = get_results_at_time(139 + byte_idx)

for r in results:

r['plaintext'] = aes_round(r['plaintext'], key0)

key1[byte_idx] = get_byte(byte_idx, results)

print('key1:', key1)

# key1 = b'\r\xc8\xbd\x84\xc4\x1dw\x9d\xe6\xcf\xf1\xc7\x06\xde\xd3\x1b'

ct = bytes.fromhex('2801dd800e7ae333258224d5cbfc5420ec72a12256bdff61814972c7f93948f8')

print(AES.new(key0 + key1, AES.MODE_ECB).decrypt(ct))

# CTF{F4aulTC0rrel4ti0n|S4f33RR0R}