Factoring in logarithmic time: a mathemagic trick

When you have an interest in cryptography, and you occasionally browse reddit, you’ve probably seen something like this before. Someone creates a new post on r/crypto or r/cryptography, claiming to be able to efficiently factor integers or RSA moduli. This then usually goes hand in hand with a serious lack of context and explanation, notation that is questionable at best, often just plain unreadable, and an aversion to providing even minimal proof by factoring an actual, cryptographically big modulus. Yet because it’s hard to understand, and sometimes there’s math involved that at first glance seems like it might have some deeper meaning, you’re left wondering, is there some insight to be found here.

Spoiler alert: nope…

Finding the good stuff

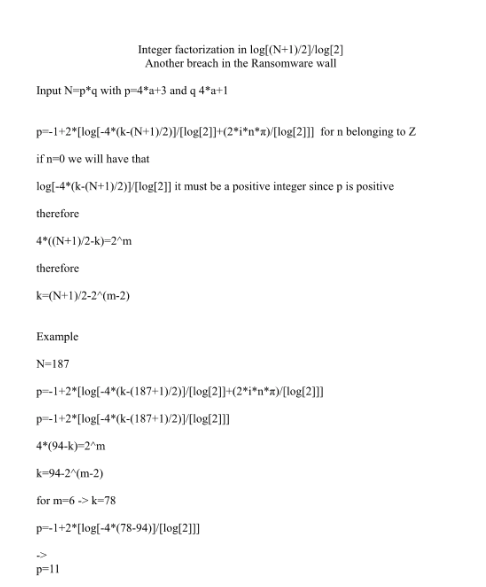

As a case study, we’ll have a closer look at this reddit post, which asks the question if this is a known attack, and then enigmatically just links to a post on linkedin. To get around my lack of linkedin account, someone was kind enough to send me the following image of the main content.

The claim in the title is immediately very interesting: “Integer factorization in log[(N + 1)/2]/log[2]”. We’ll come back to the notation in a bit, but we can see at a glance that the author claims to solve factorization in logarithmic time (so in polynomial/linear time in the number of bits, commonly known as “efficient”). Anyone with a passing knowledge on the topic of cryptography, and more in particular of RSA, will know that this is thought to be a hard problem. So either someone just made an enormous breakthrough, and we need to start changing a lot of the underlying infrastructure of most of our previously thought-to-be-secure communication, or (and this is the far more likely option), there’s something wrong with the proof.

A first look: line by line

I will try to reproduce some of the original text here. We can then have a first, line-by-line look at it, and see where the interesting parts are.

Input N=p*q with p=4*a+3 and q 4*a+1

p=-1+2*[log[-4*(k-(N+1)/2)]/[log[2]]]+(2*i*n*)/[log[2]]] for n belonging to Z

if n=0 we will have that

log[-4*(k-(N+1)/2)]/[log[2]] it must be a positive integer since p is positive

therefore

4*((N+1)/2-k)=2^m

therefore

k=(N+1)/2-2^(m-2)

And this is then followed by an example where everything is written out with a lot of detail, factoring the not-so-big number 187, while saying that m=6. The example concludes, in fact correctly, that p=11 is one of the prime factors of 187.

Line 1: perhaps it doesn’t work for general N

On the very first line, the integer being used as input to the described algorithm, $N$ is said to be of the form $pq$, with p and q prime. So far so good.

Where it gets a bit weird however, is that it is said that $p = 4a + 3$ and $q = 4a + 1$. This knowledge would of course immediately enable us to factor $N$ from the quadratic equation arising from the twin prime substitution $q = p + 2$. Let’s assume this is just some unfortunate notation, and what’s in fact meant is that $p \equiv 3 \pmod 4$ and $q \equiv 1 \pmod 4$. Reading this, we know we might want to keep an eye out if this assumption appears anywhere later on, or if it’s even more general, and all that’s needed is that $p$ and $q$ are simply odd primes.

Line 2: a wild formula appeared

The mathematical notation is not very great, so let’s first try to make it a bit more readable. We quickly spot a log[...]/log[2], which is simply $\log_2(\ldots)$. From there, most of it is fairly easily transcribed and rendered with the ever-magical $\LaTeX$:

We of course wonder where exactly this magical beast came from in the first place. We see some things that might point us to deeper insight. The $2\pi i n$, looks a lot like what we might find when a Fourier transform would be involved somehow. Especially so when we observe that this is divided by $\ln 2$, but is itself not embedded in some form of log, implying it would have originally actually been $\exp(2\pi i n)$. Let’s leave it at this for our initial exploration, and perhaps come back to this later. Take some care to not confuse the upper case $N$ with its lowercase brother $n$.

Line 3/4: let’s just ignore some things

Line two states if n=0, which begs the question: why would you just be allowed to do that. A somewhat convincing argument for this comes from the same line of thought as the next part. If we choose any other (integer) value for $n$, then $p$ would not be an integer, but some complex number. Since we know $p$ is however a prime factor, and an integer at that, we’re indeed safe to assume that $n = 0$. The resulting formula seems valid after making this substitution, so don’t seem to be any big problems with this line. Some better justification would of course be nice to read when making this kind of assumptions.

Line 5-9: the power of two

In the formula on line 2, some number $k$ appears, its origins still unknown. By the observation (which we used above too) that $p$ is necessarily integer, we know that \(\log_2\left(-4\left(k - \frac{N + 1}{2}\right)\right)\) should be an integer, and as such \(2^m = -4(k - \frac{N+1}{2})\) should be a perfect power of 2. Transforming this equality correctly, indeed gives us that \(k = -\frac{2^m - 4\frac{N+1}{2}}{4} = \frac{N + 1}{2} - 2^{m-2}.\)

Efficiency?

Without going for an extremely deep analysis, and without even being sure yet of overall correctness, let’s have a look at why this might work in logarithmic time. The algorithm seems to hinge on finding the correct value for our unknown $m$, which in turns efficiently gives us $k$ and $p$. If we take the seemingly reasonable assumption that $m - 2, k > 0$, it follows that there are at most $\mathcal{O}(\log N)$ distinct values for $m$ with which this holds.

The rabbit from the hat

We might be tempted now to look further at this wonderful starting point that gives us some closed form formula for $p$, with only the single unknown variable $k$, which we apparently could find efficiently too. That way, unfortunately, only madness, confusion and disappointment lie. By trying to find deeper mathematical truth, we’ve almost missed the little trick that makes all of this clockwork go round.

Let’s look at again at how we compute $k$, and what we do with it afterwards:

\[k = \frac{N + 1}{2} - 2^{m-2} \quad\text{and}\quad p = 2\log_2\left(4\left(\frac{N+1}{2} - k\right)\right) - 1\]Let’s collapse this a bit.

\[p = 2\log_2\left(4\left(\frac{N+1}{2} - \frac{N+1}{2} + 2^{m-2}\right)\right) - 1 = 2\log_2(2^m) - 1\]And now it’s all very clear: as we vary $m$ to try and find the “correct” value, that gives us the good value for $k$, we’re just trying all odd numbers $2m - 1$ by trial division! The entire starting point seems to be there to distract us, adding useless, but mathematically interesting looking, extra elements such as the seeming reference to Fourier transforms, obscuring some the text-only formula some more by writing $\log_2 x$ as $\frac{\log x}{\log 2}$, and overall needlessly complicating things.

Taking the first $\mathcal{O}(\log N)$ odd numbers will be enough to factor most toy examples people would be likely to try this with at first, giving false confidence in the ability of this algorithm to indeed factor RSA moduli. It hardly need be said, for cryptographically secure $N$, this algorithm would not find a factor in any reasonable time.

Conclusion

In the end, this is a fun mathematical magic trick. As most magic tricks, it relies on some misdirection, and if you pay enough attention, you can try to spot where the real switcharoo happens. I too, took the scenic route in this article, roughly following along the way I originally approached this when I at first looked at this problem, writing my thoughts in the cryptohack discord chat as I went along. I hope you enjoyed it nonetheless, and that perhaps you won’t back down from a little analysis of your own next time you encounter something like this (assuming you’ve got a bit of spare time to dedicate to it, of course).